The eyes are perhaps the most important part of the human body. In essence, the eyes allow the brain to see and therefore interface with the outside world. The eyes convert the information viewed into mental images .These images go on to become the basis for our memories, influencing our actions, choices and ultimately who we are. However, the eyes are a flawed device. At times, the eyes will miss a particular detail that in turn will affect the memory created of that certain moment in time; creating an incomplete mental memory. With the advent of the photograph, the eye’s shortcomings in capturing an external moment in its entirety seemed like a thing of the past. However, although the photograph provides a literal reproduction of an external scene, without some sort of mental connection to provide context for the image, it too is incomplete. Even then, the context created by memories, fueled by the viewer’s emotions and individual biases, also influences the way in which an image is viewed. This disconnection between photography and memory plays an important part in both in Michelangelo Antonioni’s

Blow-Up (1966) and Christopher Nolan’s

Memento (2000).

In Antonioni’s

Blow-Up, the protagonist is a fashion photographer who also takes pictures of random scenes in everyday life. One day, he photographs two lovers in a park. He is later confronted by the angry woman in the picture who demands that he give the photographs he took. Ultimately, it is revealed that he unwittingly photographed a murder and the photographer only becomes aware of what he has just witnessed after examining the photographs in detail by “blowing them up.” Here, we see where the eyes as a camera fail. In psychology, this phenomenon is called change blindness. Change blindness is defined as “failure to observe large changes in the vision field that occur simultaneously with brief disturbances.” The photographer doesn’t realize the change in scene until he goes back and examines the literal reproduction created by the photograph. Only then does he come to understand the full extent of what he witnessed.

In this respect, the photograph is treated as documentation; proof verifying that what one saw was real and indeed did happen. Upon first blowing up the images, the photographer believes that he has accidentally saved someone’s life by his presence at the park. He excited calls his editor to tell him this new account he has constructed both from his memory of the event and this new narrative created from cross referencing these new realities which he observes with each succeeding enlargement of the prints. Upon zooming in further, he realizes that he did not in fact save someone’s life, he saw someone murdered. He confirms this new narrative created by the images by finding the body in the same spot the images placed the body in. When he returns home, the prints and photographs are gone and the body disappears the next morning, leaving no proof but his memories of the events that transpired.

In

Memento, the photograph’s use as a memory tool is even more literal and plays an integral part in the narrative. The protagonist goes by the name of Leonard. One night, he and his wife were attacked at home. In the attack, Leonard was critically hurt and begins to suffer from anterograde amnesia. Anterograde amnesia leaves Leonard with the inability to create new memories after the event. As he seeks vengeance in finding one of the attackers, Leonard begins keeping track of his daily activities and people he meets by getting tattoos and keeping an index of Polaroid pictures with the names of people he meets, as well as any relevant information. Leonard literally carries with him his memories in his pocket wherever he goes.

However, these images also prove to be an unreliable source of information and a poor substitute for real memories. It is revealed that Leonard had already killed the man responsible for the attack a year before the events of the film and that the man who helped him (who goes by the name of Teddy) has since been manipulating him into killing other men for profit, all under the pretense of aiding Leonard’s quest for revenge.

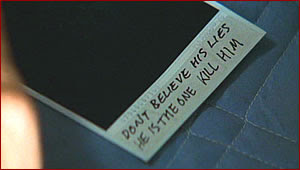

At the start of the film which chronologically takes place at the end of the story, Leonard kills Teddy and takes a picture as personal evidence that he has completed his quest. However, at the end of the film which chronologically takes place at the very beginning, it is revealed that because of his amnesia, Leonard realizes that he can’t trust Teddy and writes on his Polaroid “Don’t believe his lies” and thus leads to the events depicted at the beginning of the film. The photographs are meaningless without some sort of memory or socially constructed context to connect them to. It isn’t until Leonard can write someone’s name and why they are relevant to him that the pictures are of any use to him.