Report 1: Apparatus Fundamentals / Historical Examples

MAT255 Techniques, History & Aesthetics of the Computational Photographic Image

https://www.mat.ucsb.edu/~g.legrady/aca ... s255b.html

Please provide a response to any of the material covered in this week's two presentations by clicking on "Post Reply". Consider this to be a journal to be viewed by class members. The idea is to share thoughts, other information through links, anything that may be of interest to you and the topic at hand.

Report for this topic is due by April 15, 2022 but each of your submissions can be updated throughout the length of the course.

Report 1: Apparatus Fundamentals / Historical Examples

-

siennahelena

- Posts: 8

- Joined: Tue Mar 29, 2022 3:33 pm

Re: Report 1: Apparatus Fundamentals / Historical Examples

*** Please see revised version below in bold****

Something that was fascinating to me in this week’s lectures was how photography was used as a part of the colonization of the Western United States. We briefly discussed the photography of Edward C. Curtis and how his portraits of Native Americans have a controversial history. Curtis sought to document the lives and culture of Native Americans before they “disappeared” and “vanished”. Thus, with funding from JP Morgan, Curtis eventually amassed 40,000 photographs of 80 different tribes along with notes, recordings, and sketches. Eventually, he created a volume of books with 2,000 of these photographs entitled “The North American Indian”.

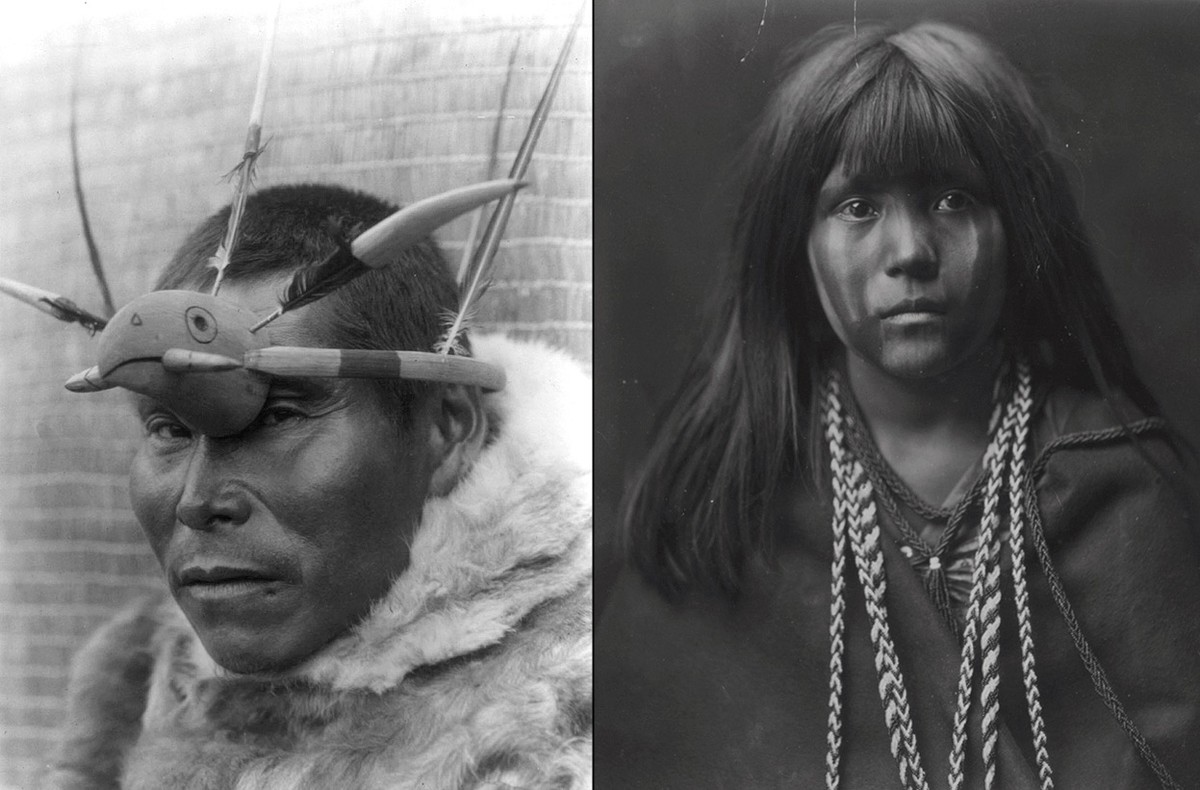

Left: Nunivak Island man, wearing headdress with a wooden bird head in front, ca. 1929. Right: Mosa, Mojave, ca. 1903 retrieved from https://www.theatlantic.com/photo/2013/ ... go/100489/

Wedding guests, Kwakiutl people in canoes, British Columbia, ca. 1914 retrieved from https://www.theatlantic.com/photo/2013/ ... go/100489/

Personally, I find it difficult to fully understand Curtis’ intentions. A significant amount of backlash against Curtis’ work is that his photographs perpetuated the westernized, white view of the “noble savage”. Indeed, many critics remark how Curtis staged many of his photos to present a romanticized view of Native Americans. For example, below is Curtis’ photo “In the Piegan Lodge”. The main difference is that in the second image, Curtis removed the clock, and this was the final published version of the photograph.

In a Piegan Lodge, by Edward S. Curtis, 1910. Retrieved from https://daily.jstor.org/edward-s-curtis ... s-reality/

Writings from Curtis also distinctly demonstrate how his sympathy for Native Americans could not be separated from his own colonial, white perspective, as this excerpt from an article he wrote illustrates:

However, the work that Curtis did includes some of the only records we have of many Indigenous Americans before they were forced onto reservations. Beyond photography, for example, Curtis also recorded many tribes spoken languages and songs. Furthermore, Curtis dedicated his life to this work and, despite being able to secure funding for his project, he was not compensated for a significant period of time. Thus, the complexity of Curtis and his documentation cannot be so quickly dismissed.

That being said, Curtis’ works also remind me of the documentary “Nanook of the North” which similarly sought to capture the lives of indigenous peoples of the Canadian Arctic. Robert J. Flaherty, the documentarian who created the film, fictionalized a significant amount of the film including the cultural practices of the Innuits he followed. For instance, Flaherty staged the film so that his subjects used harpoons to hunt and wore traditional clothing though by the time the film was made Innuits used rifles to hunt and often wore Western clothing. However, despite the fabrication sof the film, “Nanook of the North” is regarded as the basis for documentary inspiring several other non-fiction filmmakers and serving as the foundation for the documentary film genre.

You can watch the whole film on Youtube here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lkW14Lu1IBo

It brings to light the idea of power and documentation. How can we ever separate the values, biases, and beliefs held by the photographer from the images they choose to capture? But, how can we also appreciate this work as preserving a historical record? When so much of history is understood through photographs and images, then is our history dictated by those who happen to capture these moments? Furthermore, whose images are the ones chosen and championed to represent history?

References:

Something that was fascinating to me in this week’s lectures was how photography was used as a part of the colonization of the Western United States. We briefly discussed the photography of Edward C. Curtis and how his portraits of Native Americans have a controversial history. Curtis sought to document the lives and culture of Native Americans before they “disappeared” and “vanished”. Thus, with funding from JP Morgan, Curtis eventually amassed 40,000 photographs of 80 different tribes along with notes, recordings, and sketches. Eventually, he created a volume of books with 2,000 of these photographs entitled “The North American Indian”.

Left: Nunivak Island man, wearing headdress with a wooden bird head in front, ca. 1929. Right: Mosa, Mojave, ca. 1903 retrieved from https://www.theatlantic.com/photo/2013/ ... go/100489/

Wedding guests, Kwakiutl people in canoes, British Columbia, ca. 1914 retrieved from https://www.theatlantic.com/photo/2013/ ... go/100489/

Personally, I find it difficult to fully understand Curtis’ intentions. A significant amount of backlash against Curtis’ work is that his photographs perpetuated the westernized, white view of the “noble savage”. Indeed, many critics remark how Curtis staged many of his photos to present a romanticized view of Native Americans. For example, below is Curtis’ photo “In the Piegan Lodge”. The main difference is that in the second image, Curtis removed the clock, and this was the final published version of the photograph.

In a Piegan Lodge, by Edward S. Curtis, 1910. Retrieved from https://daily.jstor.org/edward-s-curtis ... s-reality/

Writings from Curtis also distinctly demonstrate how his sympathy for Native Americans could not be separated from his own colonial, white perspective, as this excerpt from an article he wrote illustrates:

“The Indians of North America are vanishing. Within the span of a few generations, they have crumbled from their pride and power into pitifully small numbers, painful poverty, and sorry weakness. A few generations more will see quite bared of them the land they held in exclusive sovereignty when we white men first discovered it. A vanishing race! There is a majestic pathos in the words; a tragedy so great that it must be regarded as an epoch-making matter.” - From Hampton Magazine article "The Vanishing Redman" (1912) https://www.curtislegacyfoundation.org/ ... fbf1c1.pdf

However, the work that Curtis did includes some of the only records we have of many Indigenous Americans before they were forced onto reservations. Beyond photography, for example, Curtis also recorded many tribes spoken languages and songs. Furthermore, Curtis dedicated his life to this work and, despite being able to secure funding for his project, he was not compensated for a significant period of time. Thus, the complexity of Curtis and his documentation cannot be so quickly dismissed.

That being said, Curtis’ works also remind me of the documentary “Nanook of the North” which similarly sought to capture the lives of indigenous peoples of the Canadian Arctic. Robert J. Flaherty, the documentarian who created the film, fictionalized a significant amount of the film including the cultural practices of the Innuits he followed. For instance, Flaherty staged the film so that his subjects used harpoons to hunt and wore traditional clothing though by the time the film was made Innuits used rifles to hunt and often wore Western clothing. However, despite the fabrication sof the film, “Nanook of the North” is regarded as the basis for documentary inspiring several other non-fiction filmmakers and serving as the foundation for the documentary film genre.

You can watch the whole film on Youtube here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lkW14Lu1IBo

It brings to light the idea of power and documentation. How can we ever separate the values, biases, and beliefs held by the photographer from the images they choose to capture? But, how can we also appreciate this work as preserving a historical record? When so much of history is understood through photographs and images, then is our history dictated by those who happen to capture these moments? Furthermore, whose images are the ones chosen and championed to represent history?

References:

- Edward Curtis and the Background of the Collection | Articles and Essays | Curtis (Edward S.) Collection | Digital Collections | Library of Congress [Web page]. (n.d.). Retrieved April 11, 2022, from Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA website: https://www.loc.gov/collections/edward- ... ollection/

- King, G. (n.d.). Edward Curtis’ Epic Project to Photograph Native Americans. Retrieved April 11, 2022, from Smithsonian Magazine website: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/ ... 162523282/

- Meier, A. C. (2018, May 18). Edward S. Curtis: Romance vs. Reality. Retrieved April 11, 2022, from JSTOR Daily website: https://daily.jstor.org/edward-s-curtis ... s-reality/

- Robert Flaherty | American explorer and filmmaker | Britannica. (n.d.). Retrieved April 11, 2022, from https://www.britannica.com/biography/Robert-Flaherty

Last edited by siennahelena on Tue Apr 26, 2022 12:25 pm, edited 1 time in total.

-

ashleybruce

- Posts: 11

- Joined: Thu Jan 07, 2021 2:59 pm

Re: Report 1: Apparatus Fundamentals / Historical Examples

One of the topics I wanted to explore more was photographic manipulation and its impact on society.

As photography was beginning, there was the idea of the "photograph" as "real life." The image being created was capturing a specific moment in time, exactly as it was; a "true image." But this idea of a true image quickly became a false image with the idea of photographic manipulation. In its early days, photo manipulation was a task achieved by manual darkroom techniques. One of the earliest examples of this is from around 1860, where Abraham Lincoln's head was put onto John Calhoun's body.

Although the prospects of photo manipulation appeared early on, because the means to do it were fairly difficult, manipulated photos were not very widespread.

As technology improved and photography became more popular in the early 1900s, personal cameras became more common. People from all backgrounds were able to have their own camera and capture their own slices of life. These slices of life quickly became more heartbreaking as political tensions rose, and eventually resulting in World War I. Widespread camera usage resulted in a better documentation of battle, images that showcased how war was from the front lines.

These pictures could not only give others a better idea of what was happening, but could do it in a way that more people believed it as well. People had their own cameras and were capturing their own photos, so they understood, and more importantly believed, that the photos they were being shown was real life. This willingness to believe, paired with corruption, paved the way for political leaders to use it for their agenda. For example, Joseph Stalin used photographic manipulation for propaganda purposes, erasing communists out of pictures.

Benito Mussolini removed the horse handler from the original image to portray a more heroic image of himself.

These believable, yet edited photos introduced skepticism into photojournalism at a very early time. Are the photos actually giving us the whole story? Are they even giving us a true story? Although the edits in the photos depicted above are small, they tell very different stories.

As technology continues to advance, photo manipulation has just become easier and easier to do. Yet even so, there is still such a willingness to believe that continues to be present today. One thing I am interested in exploring more as the class progresses is how these edited photos shape the views of the onlookers. What does the editor gain and the onlookers lose from these manipulations?

References:

* Analysis of Key Photo Manipulation Cases and their Impact on Photography. Jitendra Sharma & Rohita Sharma.

* Capturing Memories: Photography in WWI. Sarah Johnson. https://rememberingwwi.villanova.edu/photography/

As photography was beginning, there was the idea of the "photograph" as "real life." The image being created was capturing a specific moment in time, exactly as it was; a "true image." But this idea of a true image quickly became a false image with the idea of photographic manipulation. In its early days, photo manipulation was a task achieved by manual darkroom techniques. One of the earliest examples of this is from around 1860, where Abraham Lincoln's head was put onto John Calhoun's body.

Although the prospects of photo manipulation appeared early on, because the means to do it were fairly difficult, manipulated photos were not very widespread.

As technology improved and photography became more popular in the early 1900s, personal cameras became more common. People from all backgrounds were able to have their own camera and capture their own slices of life. These slices of life quickly became more heartbreaking as political tensions rose, and eventually resulting in World War I. Widespread camera usage resulted in a better documentation of battle, images that showcased how war was from the front lines.

These pictures could not only give others a better idea of what was happening, but could do it in a way that more people believed it as well. People had their own cameras and were capturing their own photos, so they understood, and more importantly believed, that the photos they were being shown was real life. This willingness to believe, paired with corruption, paved the way for political leaders to use it for their agenda. For example, Joseph Stalin used photographic manipulation for propaganda purposes, erasing communists out of pictures.

Benito Mussolini removed the horse handler from the original image to portray a more heroic image of himself.

These believable, yet edited photos introduced skepticism into photojournalism at a very early time. Are the photos actually giving us the whole story? Are they even giving us a true story? Although the edits in the photos depicted above are small, they tell very different stories.

As technology continues to advance, photo manipulation has just become easier and easier to do. Yet even so, there is still such a willingness to believe that continues to be present today. One thing I am interested in exploring more as the class progresses is how these edited photos shape the views of the onlookers. What does the editor gain and the onlookers lose from these manipulations?

References:

* Analysis of Key Photo Manipulation Cases and their Impact on Photography. Jitendra Sharma & Rohita Sharma.

* Capturing Memories: Photography in WWI. Sarah Johnson. https://rememberingwwi.villanova.edu/photography/

-

nataliadubon

- Posts: 15

- Joined: Tue Mar 29, 2022 3:30 pm

Re: Report 1: Apparatus Fundamentals / Historical Examples

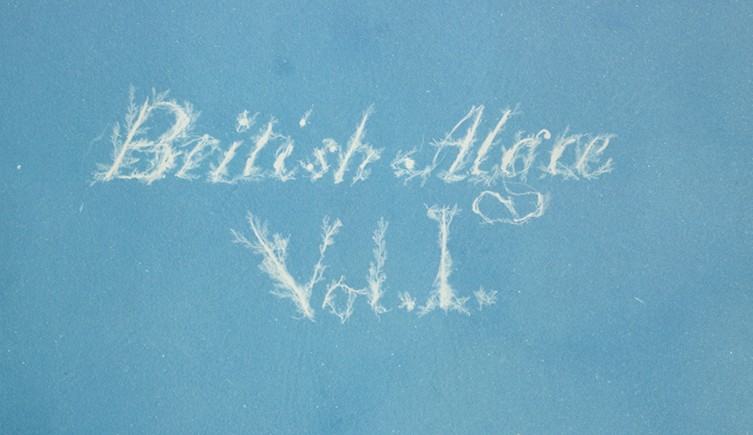

One particular topic I wanted to explore further from the past week's lectures revolves around Anna Atkins, the English botanist and photographer who famously used cyanotypes to record her scientific data. Though it was briefly mentioned, Anna Atkins is often credited as the first person to create and successfully publish a photographic book titled Photographs of British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions (1843). What appears rather interesting within her book is her creative means of illustrating titles; she not only used cyanotype in the practical sense of physically recording her biological data, but also in the creative sense of manually forming thin strands of seaweed to form delicate lettering.

I've personally developed my own images using cyanotypes before and can confirm that the process is much less intimidating than it may initially seem. The paper itself is coated with a chemical solution that is particularly sensitive to ultraviolet light, which gives it its signature blue color. Placing an object or negative onto the paper and then exposing the entirety to sunlight or UV light for an estimate of ten to fifteen minutes allows said object to be transferred onto the paper, quite similar to a shadow. Running the paper under water in order to wash off the original chemical coating reveals the photograph.

The cyanotype is significant in its affordability and ease, which becomes especially pivotal when understanding the historical context surrounding photography and its accessibility in the 1800s. Previous to the cyanotype, the daguerreotype was invented in 1837; however, equipping the daguerreotype was overall a fairly expensive process in addition to being a complicated one as well. Therefore, only the most knowledgeable, experienced, and wealthy could take advantage of such a device. Though the cyanotype is immensely different from the daguerreotype, it nonetheless allowed for the affordability and accessibility of photography as a whole.

References:

I've personally developed my own images using cyanotypes before and can confirm that the process is much less intimidating than it may initially seem. The paper itself is coated with a chemical solution that is particularly sensitive to ultraviolet light, which gives it its signature blue color. Placing an object or negative onto the paper and then exposing the entirety to sunlight or UV light for an estimate of ten to fifteen minutes allows said object to be transferred onto the paper, quite similar to a shadow. Running the paper under water in order to wash off the original chemical coating reveals the photograph.

The cyanotype is significant in its affordability and ease, which becomes especially pivotal when understanding the historical context surrounding photography and its accessibility in the 1800s. Previous to the cyanotype, the daguerreotype was invented in 1837; however, equipping the daguerreotype was overall a fairly expensive process in addition to being a complicated one as well. Therefore, only the most knowledgeable, experienced, and wealthy could take advantage of such a device. Though the cyanotype is immensely different from the daguerreotype, it nonetheless allowed for the affordability and accessibility of photography as a whole.

References:

- “Anna Atkins and the First Book of Photographs.” Natural History Museum, https://www.nhm.ac.uk/discover/anna-atk ... hotography.

- “How to Make Cyanotypes.” Parallax Photographic Coop, 3 May 2021, https://parallaxphotographic.coop/how-t ... 20together.

- Kok, Jenevieve. “Brilliance in Blue - What Are Cyanotypes?” The Artling, 4 Dec. 2020, https://theartling.com/en/artzine/what- ... et%20light.