wk3 10.07/10.09: Digital Image, Time, Space, Interactivity, Narrative

wk3 10.07/10.09: Digital Image, Time, Space, Interactivity, Narrative

wk3 10.07/10.09: Digital Image, Time, Space, Interactivity, Narrative

The aim of the M200a Art & Technology is to give a broad overview of the field of computer-based art and its relationship to technological development. One approach is to consider how artists use the evolving technologies to:

1) Experiment and explore ideas and aesthetics (play of the imagination)

2) Arrive at new ways of creating and representing the world that could not have been done before

This week we are looking at examples of time-based art, and artworks that consider various methods for interacting with computer controls. Unfortunately, we are limited by time, so it is not possible to show the multitudes of works in existance. The lecture today features a selection of works that I have come across over time, and which I consider relevant.

For the assignment, select and discuss a few examples of interest to you, and/or possible underlying themes you see in a number of the works.

The aim of the M200a Art & Technology is to give a broad overview of the field of computer-based art and its relationship to technological development. One approach is to consider how artists use the evolving technologies to:

1) Experiment and explore ideas and aesthetics (play of the imagination)

2) Arrive at new ways of creating and representing the world that could not have been done before

This week we are looking at examples of time-based art, and artworks that consider various methods for interacting with computer controls. Unfortunately, we are limited by time, so it is not possible to show the multitudes of works in existance. The lecture today features a selection of works that I have come across over time, and which I consider relevant.

For the assignment, select and discuss a few examples of interest to you, and/or possible underlying themes you see in a number of the works.

George Legrady

legrady@mat.ucsb.edu

legrady@mat.ucsb.edu

-

shashank86

- Posts: 9

- Joined: Wed Oct 01, 2025 2:36 pm

Re: wk3 10.07/10.09: Digital Image, Time, Space, Interactivity, Narrative

TIME-BASED ART & INTERACTIVITY

Time-based art often emerges when an artist, as both a creator and a human being, seeks to explore, experience, and engage with a wide range of phenomena, both naturally occurring and human-made. Within this form, traditional aesthetic boundaries tend to blur more than in other artistic practices, as the number of interacting variables is significantly greater, each operating across multiple dimensions. This complexity can make the work feel multifaceted or even diffuse if the elements are not thoughtfully connected or if their functions are not aligned coherently. Although time-based art appears to operate without strict rules, its effectiveness ultimately depends on how convincingly and intentionally these components integrate to form the final experience.

From observation, much time-based art aligns closely with conceptual art, yet it often incorporates functionality as well. As this practice evolves, it has the potential to yield techniques applicable beyond the realm of art. Such utilitarian outcomes risk diminishing expressive depth. However, the artistic value persists and may even deepen when the work produces something meaningful or operational. In this sense, “expression” evolves rather than disappears, transforming the artist into a triggering point within an ongoing process—an idea reminiscent of entropy, where separation or transformation marks not an ending, but the beginning of something new. This shift may signal the end of one form of expression and the start of a new application, or the end of one aesthetic mode and the emergence of another.

Returning to the notion of time-based art, its potential for expansion is vast, yet its meaning stabilizes only when grounded in a coherent truth or intention. Despite the complexity of its components, this art form represents a collective embodiment of human and natural innovation; even when created by a single individual, it carries the influence of many indirect contributors. In this way, time-based art becomes symbolic of shared human effort and environmental forces, granting it a distinctive capacity to redefine concepts such as truth, meaning, and beauty, or to catalyze broader cultural transformations.

What remains striking is that, amid all this complexity, storytelling continues to function as a powerful and persistent force, even within time-based media. This highlights the idea that narrative is perhaps one of the most fundamental structures guiding artistic expression, with the techniques and engineering behind the work serving in supportive roles.

Finally, as a reminder drawn from influential practitioners, one might look toward artists such as David Lynch, whose approach exemplifies how time-based art can intertwine narrative, atmosphere, and experiment to profound effect

Nam June Paik’s TV Buddha (1974),

![Image]()

It consists of a Buddha statue watching its own live video image on a television monitor. The work blurs the boundaries between technology, spirituality, time, and self-reflection, embodying how time-based media integrates multiple dimensions into a single experience. Its looping feedback system also resonates with my arguments about expression evolving into function, the collective nature of time-based creation, and the persistence of storytelling even in non-narrative forms.

Time-based art often emerges when an artist, as both a creator and a human being, seeks to explore, experience, and engage with a wide range of phenomena, both naturally occurring and human-made. Within this form, traditional aesthetic boundaries tend to blur more than in other artistic practices, as the number of interacting variables is significantly greater, each operating across multiple dimensions. This complexity can make the work feel multifaceted or even diffuse if the elements are not thoughtfully connected or if their functions are not aligned coherently. Although time-based art appears to operate without strict rules, its effectiveness ultimately depends on how convincingly and intentionally these components integrate to form the final experience.

From observation, much time-based art aligns closely with conceptual art, yet it often incorporates functionality as well. As this practice evolves, it has the potential to yield techniques applicable beyond the realm of art. Such utilitarian outcomes risk diminishing expressive depth. However, the artistic value persists and may even deepen when the work produces something meaningful or operational. In this sense, “expression” evolves rather than disappears, transforming the artist into a triggering point within an ongoing process—an idea reminiscent of entropy, where separation or transformation marks not an ending, but the beginning of something new. This shift may signal the end of one form of expression and the start of a new application, or the end of one aesthetic mode and the emergence of another.

Returning to the notion of time-based art, its potential for expansion is vast, yet its meaning stabilizes only when grounded in a coherent truth or intention. Despite the complexity of its components, this art form represents a collective embodiment of human and natural innovation; even when created by a single individual, it carries the influence of many indirect contributors. In this way, time-based art becomes symbolic of shared human effort and environmental forces, granting it a distinctive capacity to redefine concepts such as truth, meaning, and beauty, or to catalyze broader cultural transformations.

What remains striking is that, amid all this complexity, storytelling continues to function as a powerful and persistent force, even within time-based media. This highlights the idea that narrative is perhaps one of the most fundamental structures guiding artistic expression, with the techniques and engineering behind the work serving in supportive roles.

Finally, as a reminder drawn from influential practitioners, one might look toward artists such as David Lynch, whose approach exemplifies how time-based art can intertwine narrative, atmosphere, and experiment to profound effect

Nam June Paik’s TV Buddha (1974),

It consists of a Buddha statue watching its own live video image on a television monitor. The work blurs the boundaries between technology, spirituality, time, and self-reflection, embodying how time-based media integrates multiple dimensions into a single experience. Its looping feedback system also resonates with my arguments about expression evolving into function, the collective nature of time-based creation, and the persistence of storytelling even in non-narrative forms.

Last edited by shashank86 on Sat Nov 15, 2025 12:31 pm, edited 3 times in total.

Re: wk3 10.07/10.09: Digital Image, Time, Space, Interactivity, Narrative

Legible City (1989)

I am extremely interested in this work with my background as an urban designer. The work is location-based with three famous cities- Manhattan, Amsterdam and Karlsruhe. In the work, they are all cities constructed with words and stories. Manhattan consists of 8 different stories and the characters are ranging from the most famous architect Frank Lloyd Wright, the current president of the US, Trump to people who don't have a name mentioned but very common in the city of Manhattan, like a taxi driver, a tour guide. They are non-related with each other at the first glance but they all part of Manhattan, which provides different perspectives of reading one of the most great cities in the world. I feel very resonated with the project as my master thesis explored a similar topic of how to construct reading of a place from multiple perspectives, especially the ones who are not considered very important persons, like the tour guide, the taxi driver.

For the Amsterdam and Karlsruhe, there are exploration of how to rebuild historical cities in the virtual environment. The city boundary is the 1800's boundary instead of the current city, and the texts visualization is a manifest of architectures in the city with same heights, layout, even the colors of the texts matches the buildings. Biking as a way to travel and interact with the cities is very clever and quite suits the scenario, especially in Amsterdam, and the attention to architectural scale make the experience both hyper-reality and authentic.

David Rokeby - San Marco Flow

For me, San Marco Flow is another way of exploring cityscape, focusing on time domain. By layering images and sharpen edges, the work visualizes the movement of people and pigeons using San Marco Plaza. It present a record of the temporary social architecture that is shaped by the permanent physical architecture of the piazza.

The two works are both interpretations of spatial and movement experience in urban space. The Legible City focuses on personal interaction and travel through multiple spaces, while San Marco Flow focuses on multiple users within a single space. I think the contract is very interesting.

I am extremely interested in this work with my background as an urban designer. The work is location-based with three famous cities- Manhattan, Amsterdam and Karlsruhe. In the work, they are all cities constructed with words and stories. Manhattan consists of 8 different stories and the characters are ranging from the most famous architect Frank Lloyd Wright, the current president of the US, Trump to people who don't have a name mentioned but very common in the city of Manhattan, like a taxi driver, a tour guide. They are non-related with each other at the first glance but they all part of Manhattan, which provides different perspectives of reading one of the most great cities in the world. I feel very resonated with the project as my master thesis explored a similar topic of how to construct reading of a place from multiple perspectives, especially the ones who are not considered very important persons, like the tour guide, the taxi driver.

For the Amsterdam and Karlsruhe, there are exploration of how to rebuild historical cities in the virtual environment. The city boundary is the 1800's boundary instead of the current city, and the texts visualization is a manifest of architectures in the city with same heights, layout, even the colors of the texts matches the buildings. Biking as a way to travel and interact with the cities is very clever and quite suits the scenario, especially in Amsterdam, and the attention to architectural scale make the experience both hyper-reality and authentic.

David Rokeby - San Marco Flow

For me, San Marco Flow is another way of exploring cityscape, focusing on time domain. By layering images and sharpen edges, the work visualizes the movement of people and pigeons using San Marco Plaza. It present a record of the temporary social architecture that is shaped by the permanent physical architecture of the piazza.

The two works are both interpretations of spatial and movement experience in urban space. The Legible City focuses on personal interaction and travel through multiple spaces, while San Marco Flow focuses on multiple users within a single space. I think the contract is very interesting.

-

jintongyang

- Posts: 10

- Joined: Wed Oct 01, 2025 2:38 pm

Re: wk3 10.07/10.09: Digital Image, Time, Space, Interactivity, Narrative

I’m very interested in full-body immersive experience with affective computing. In the 5th episode of Black Mirror Season 7, there is a technology called Eulogy that uses brainwave control and AI generation to turn old photos into 3D spaces that people can actually walk into, so they can relive their lost memories (Netflix's report: https://www.netflix.com/tudum/articles/ ... -explained). Even though it’s fictional, I think it shows the most fascinating part of time-based arts — using digital technology to bring still images back to life. Time, space, and emotion inside an image are no longer just things to look at, but something that can be experienced and rebuilt.

After photography became digital, the information inside an image (both the pixels and its cultural or emotional meaning) can be encoded, analyzed, edited, and regenerated. This shift has opened up new possibilities for art. Artists can now use multimodal and immersive ways to reinterpret time and space, creating non-linear and rule-breaking worlds that allow audiences to physically feel and sense the flow of information.

Among this week’s works, I was particularly drawn to David Rokeby’s San Marco Flow (2004) (http://www.davidrokeby.com/smf.html).Using algorithms to analyze the trajectories, speeds, and densities of people moving through Piazza San Marco in Venice, Rokeby overlays moments from different times into the same spatial frame, creating a “river of time.” The work mixes stillness and motion, becoming both a record of real time and an abstract visualization. As light and shadow interact with the viewer’s body, the viewers become both observers and data points, transforming the medium of immersion from a physical space into a dynamic information system.

I think this kind of work explores how humans and digital systems coexist. In the near future, how can digital media fold or expand time and space? And how can information respond to emotion and body in real time?

Rafael Lozano-Hemmer’s Body Movies (2001) (Fig.1) is a similar example. He projected thousands of portraits taken from the streets onto building facades. The portraits only appear inside the big shadows of the passersby (their silhouettes become triggers for the images to emerge). As people move, new faces are revealed or hidden, creating a real-time narrative between light and movement. The work makes the public space an interactive stage, where the audience becomes both the subject and the medium — an early example combining HCI and public art.

Fig.1. Rafael Lozano-Hemmer, Body Movies (2001), https://www.lozano-hemmer.com/body_movies.php

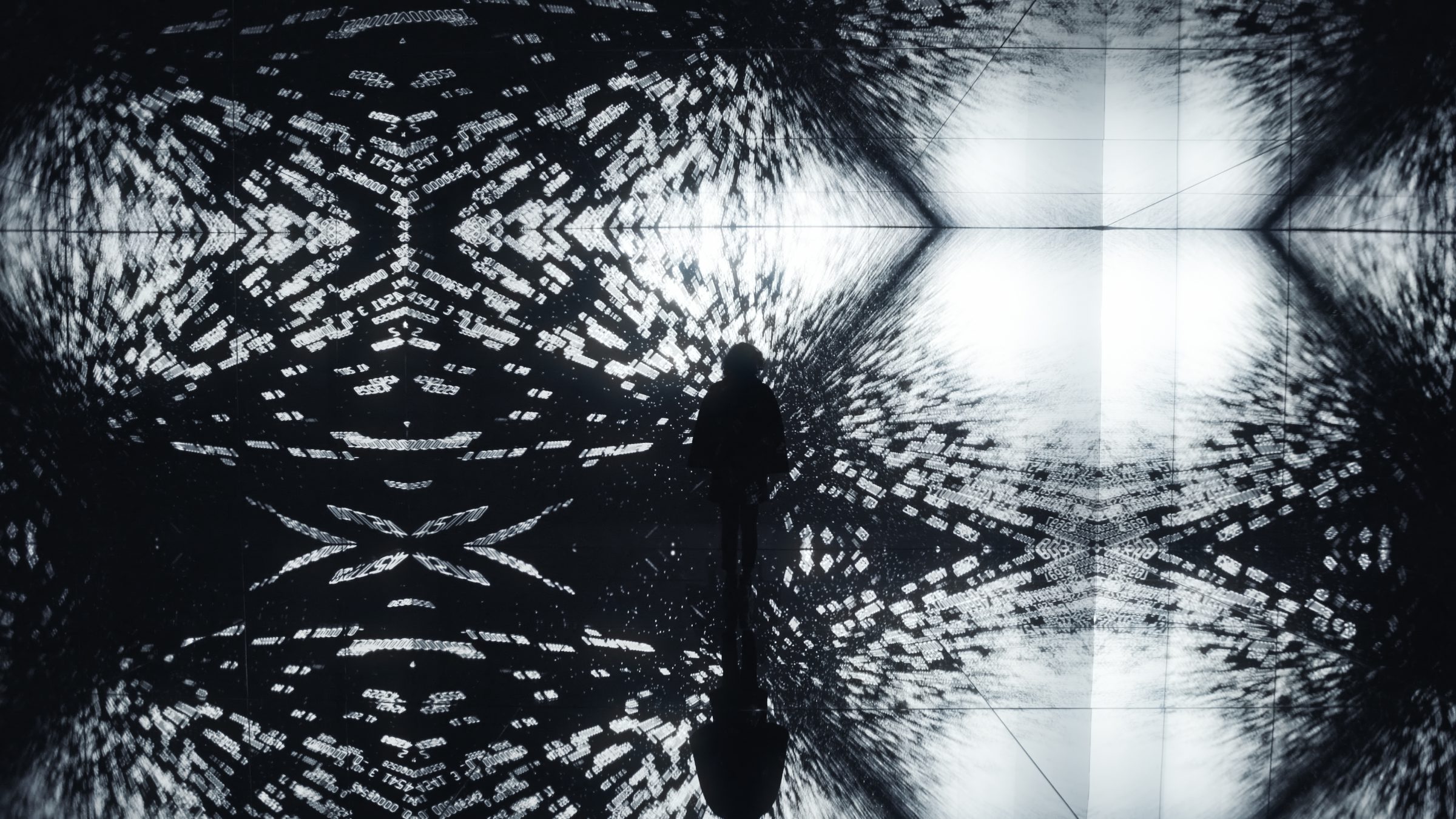

Refik Anadol develops relevent concept on a larger scale. With AI and big data, he transforms architecture into “buildings of data.” Works like Melting Memories (2018) (Fig.2) and Data Universe (2021) (Fig.3) show what he calls “information fluidity.” He turns memories, neural data, or environmental data into moving light patterns, creating an algorithmic sense of immersion. This also shows how immersion expands from the body into the data world.

Fig.2. Refik Anadol, Melting Memories (2018), https://refikanadol.com/works/melting-memories/

Fig.3. Refik Anadol, Data Universe (2021), https://refikanadol.com/works/pladis-data-universe/

Meanwhile, artists are exploring real-time feedback through physical installations. For example, Daniel Rozin’s Wood Mirror (1999) (Fig.4) uses hundreds of wooden tiles that flip by motors to show the viewer’s reflection instantly. It’s both mechanical and digital — a kind of dialogue between human and machine perception.

Fig.4. Daniel Rozin, Wood Mirror (1999), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1ZPJ0U_kpNg

Lozano-Hemmer’s recent works, such as Binocular Tension (2024) and Recurrent Kafka (2025) (Fig.5), incorporate affective computing and psychological feedback systems. By collecting viewers’ physiological and emotional data in real time, the system generates continuously changing visual and sonic environments, forming an empathic loop between installation and audience, where technology doesn’t just detect emotion but also helps produce it.

Fig.5. Rafael Lozano-Hemmer, Recurrent Kafka (2025), https://www.lozano-hemmer.com/recurrent_kafka.php

These works expand the meaning of time-based art itself. Instead of a fixed timeline or duration, time here becomes a living feedback process. Human perception is now being perceived, analyzed, and rebuilt by machines, and the “time” of experience is co-created by both. Overall, immersive art today goes beyond illusion. It enters physical, emotional, and algorithmic dimensions, reorganizing time and space through AI and sensory feedback. Artists reorganize time and space, making experience itself non-linear, non-physical, yet deeply empathetic.

After photography became digital, the information inside an image (both the pixels and its cultural or emotional meaning) can be encoded, analyzed, edited, and regenerated. This shift has opened up new possibilities for art. Artists can now use multimodal and immersive ways to reinterpret time and space, creating non-linear and rule-breaking worlds that allow audiences to physically feel and sense the flow of information.

Among this week’s works, I was particularly drawn to David Rokeby’s San Marco Flow (2004) (http://www.davidrokeby.com/smf.html).Using algorithms to analyze the trajectories, speeds, and densities of people moving through Piazza San Marco in Venice, Rokeby overlays moments from different times into the same spatial frame, creating a “river of time.” The work mixes stillness and motion, becoming both a record of real time and an abstract visualization. As light and shadow interact with the viewer’s body, the viewers become both observers and data points, transforming the medium of immersion from a physical space into a dynamic information system.

I think this kind of work explores how humans and digital systems coexist. In the near future, how can digital media fold or expand time and space? And how can information respond to emotion and body in real time?

Rafael Lozano-Hemmer’s Body Movies (2001) (Fig.1) is a similar example. He projected thousands of portraits taken from the streets onto building facades. The portraits only appear inside the big shadows of the passersby (their silhouettes become triggers for the images to emerge). As people move, new faces are revealed or hidden, creating a real-time narrative between light and movement. The work makes the public space an interactive stage, where the audience becomes both the subject and the medium — an early example combining HCI and public art.

Fig.1. Rafael Lozano-Hemmer, Body Movies (2001), https://www.lozano-hemmer.com/body_movies.php

Refik Anadol develops relevent concept on a larger scale. With AI and big data, he transforms architecture into “buildings of data.” Works like Melting Memories (2018) (Fig.2) and Data Universe (2021) (Fig.3) show what he calls “information fluidity.” He turns memories, neural data, or environmental data into moving light patterns, creating an algorithmic sense of immersion. This also shows how immersion expands from the body into the data world.

Fig.2. Refik Anadol, Melting Memories (2018), https://refikanadol.com/works/melting-memories/

Fig.3. Refik Anadol, Data Universe (2021), https://refikanadol.com/works/pladis-data-universe/

Meanwhile, artists are exploring real-time feedback through physical installations. For example, Daniel Rozin’s Wood Mirror (1999) (Fig.4) uses hundreds of wooden tiles that flip by motors to show the viewer’s reflection instantly. It’s both mechanical and digital — a kind of dialogue between human and machine perception.

Fig.4. Daniel Rozin, Wood Mirror (1999), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1ZPJ0U_kpNg

Lozano-Hemmer’s recent works, such as Binocular Tension (2024) and Recurrent Kafka (2025) (Fig.5), incorporate affective computing and psychological feedback systems. By collecting viewers’ physiological and emotional data in real time, the system generates continuously changing visual and sonic environments, forming an empathic loop between installation and audience, where technology doesn’t just detect emotion but also helps produce it.

Fig.5. Rafael Lozano-Hemmer, Recurrent Kafka (2025), https://www.lozano-hemmer.com/recurrent_kafka.php

These works expand the meaning of time-based art itself. Instead of a fixed timeline or duration, time here becomes a living feedback process. Human perception is now being perceived, analyzed, and rebuilt by machines, and the “time” of experience is co-created by both. Overall, immersive art today goes beyond illusion. It enters physical, emotional, and algorithmic dimensions, reorganizing time and space through AI and sensory feedback. Artists reorganize time and space, making experience itself non-linear, non-physical, yet deeply empathetic.

Last edited by jintongyang on Thu Nov 06, 2025 10:13 am, edited 2 times in total.

Re: wk3 10.07/10.09: Digital Image, Time, Space, Interactivity, Narrative

I want to discuss two works: the first is "Granular Synthesis(Akemi Takeya)", and the second is "Steina Vasulka – Violin Power (1978)."

Granular Synthesis(Akemi Takeya)

When I saw Granular Synthesis (Akemi Takeya) in class, I was honestly shocked. I had always thought granular synthesis only existed in sound, but this was the first time I saw it used in both audio and visuals together. Also, I think granular synthesis is one of the best techniques to express time-based art. When it reconstructs and deconstructs both sound and image into micro fragments—tiny grains—and then reassembles them into new rhythmic, visual, and sonic patterns, the timeline of this artwork is being changed. Instead of showing a continuous video or a simple linear narrative, the work keeps shifting and looping, stretching time or freezing moments in ways that feel both mechanical and organic.

All these fragments—the repetition, delay, and transformation—create a sense of suspended time and explosive energy, where the audience never knows what sound or image will come next. In this way, the work easily delivers a powerful impact. For example, when I first saw the scream in this piece in class, it left a truly strong and lasting impression on me. (Figure1)

Personally speaking, I’ve always really liked granular synthesis, especially in the field of audio, since the sound it produces is so unique and special. Whenever I use granular synthesis, I always feel that it gives music a completely new meaning. For example, I once composed a piece called The Fragment, in which I built a granular synthesis patch in Max/MSP and used it to change the live sound of a clarinet. I chose this technique because it breaks the traditional tone of the clarinet into tiny particles, turning it into something more electronic and fragmented. To me, this process feels very similar to what’s happening today between humans and rapidly developing technology—the appearance of new technology constantly reshapes and even “breaks apart” people’s original way of life.

Steina Vasulka – Violin Power (1978)

The artwork Violin Power really caught my attention because this is an early and creative experiment with audiovisualisation — using a Scan Processor to control and shape the video scan lines. It’s honestly pretty amazing, especially considering that back then, computer graphics weren’t even common yet. I really like how Steina used the brightness and sound signals to change the form of the image. Compared to many modern visuals generated by sound, this feels much more direct — it actually shows what the audio wave“looks like.” (Figure 1) In another part of the piece, the sound makes the video flicker and pulse frequently (Figure 2).. For me, that flickering feels like the visual form of musical noise. Just like in audio, noise isn’t bad — it’s still a kind of music, which is just a powerful way to express the project’s mood. There’s also something deeper meaning I think, in how this work plays with space and time. For example, in one moment (Figure 3), the music triggers two cameras so that Steina’s face and back appear on the screen at the same time. I think that’s a really interesting way to merge space and alter the perception of time. As the audience, we can hear the sound instantly while seeing both sides of the performer simultaneously, which feels truly special and immersive to me.

Granular Synthesis(Akemi Takeya)

When I saw Granular Synthesis (Akemi Takeya) in class, I was honestly shocked. I had always thought granular synthesis only existed in sound, but this was the first time I saw it used in both audio and visuals together. Also, I think granular synthesis is one of the best techniques to express time-based art. When it reconstructs and deconstructs both sound and image into micro fragments—tiny grains—and then reassembles them into new rhythmic, visual, and sonic patterns, the timeline of this artwork is being changed. Instead of showing a continuous video or a simple linear narrative, the work keeps shifting and looping, stretching time or freezing moments in ways that feel both mechanical and organic.

All these fragments—the repetition, delay, and transformation—create a sense of suspended time and explosive energy, where the audience never knows what sound or image will come next. In this way, the work easily delivers a powerful impact. For example, when I first saw the scream in this piece in class, it left a truly strong and lasting impression on me. (Figure1)

Personally speaking, I’ve always really liked granular synthesis, especially in the field of audio, since the sound it produces is so unique and special. Whenever I use granular synthesis, I always feel that it gives music a completely new meaning. For example, I once composed a piece called The Fragment, in which I built a granular synthesis patch in Max/MSP and used it to change the live sound of a clarinet. I chose this technique because it breaks the traditional tone of the clarinet into tiny particles, turning it into something more electronic and fragmented. To me, this process feels very similar to what’s happening today between humans and rapidly developing technology—the appearance of new technology constantly reshapes and even “breaks apart” people’s original way of life.

Steina Vasulka – Violin Power (1978)

The artwork Violin Power really caught my attention because this is an early and creative experiment with audiovisualisation — using a Scan Processor to control and shape the video scan lines. It’s honestly pretty amazing, especially considering that back then, computer graphics weren’t even common yet. I really like how Steina used the brightness and sound signals to change the form of the image. Compared to many modern visuals generated by sound, this feels much more direct — it actually shows what the audio wave“looks like.” (Figure 1) In another part of the piece, the sound makes the video flicker and pulse frequently (Figure 2).. For me, that flickering feels like the visual form of musical noise. Just like in audio, noise isn’t bad — it’s still a kind of music, which is just a powerful way to express the project’s mood. There’s also something deeper meaning I think, in how this work plays with space and time. For example, in one moment (Figure 3), the music triggers two cameras so that Steina’s face and back appear on the screen at the same time. I think that’s a really interesting way to merge space and alter the perception of time. As the audience, we can hear the sound instantly while seeing both sides of the performer simultaneously, which feels truly special and immersive to me.

Re: wk3 10.07/10.09: Digital Image, Time, Space, Interactivity, Narrative

The concept of time and space in visual installations depend on how interesting or immersive one finds the artwork, in my opinion. If someone is only taking a glance while passing through, their presence will be limited to the here and now in the location. I remember seeing one of both Nam June Paik and Bill Viola’s works when I was working at the Memorial Art Gallery (MAG) in Rochester, NY.

I remember seeing a bunch of other versions of the Bakelite Robot online but the version in the MAG had 7 screens that each displayed colourful moving images reminiscent of the Windows Media Player sound visualisations. The “robot” aspect of the work came from the humanoid shape created by the merging of multiple radios. It had a head, a torso, arms, and legs, and the small TV screens were placed into the hollow circular spaces left from the dials removed from the radios.

For me personally, this humanoid presentation was more impactful than seeing a bunch of screens on a wall. Humans tend to anthropomorphise inanimate objects all the time. I believe that having this artwork shaped like a tiny human helped museum-goers feel a deeper connection than they would have felt normally, in the given time and space.

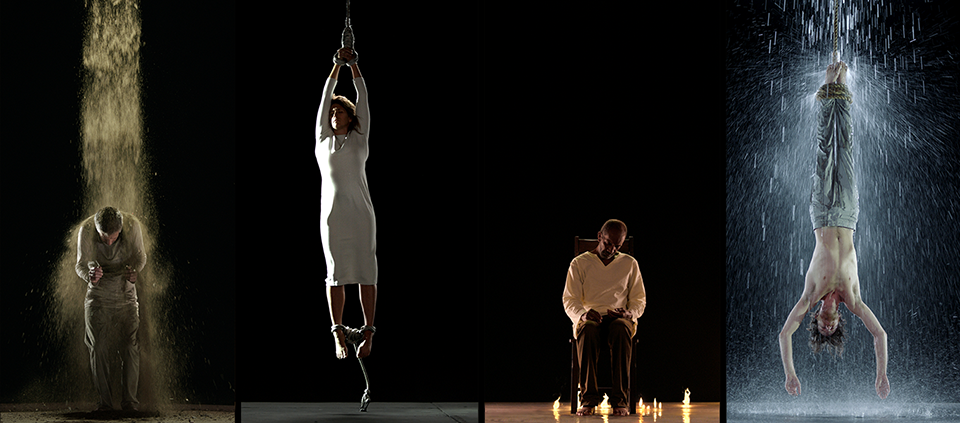

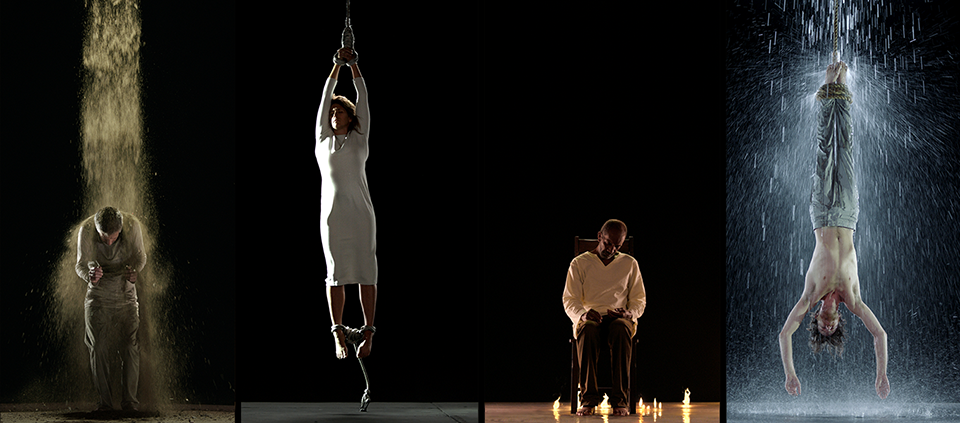

The second example, again in MAG, was the video installation of Bill Viola called “Martyrs”. This particular work was presented in the form of four vertical HD flat-screen monitors next to each other. On each screen, there was a human figure gradually being engulfed in either water, earth, fire, or air. I remember seeing an elemental approach in the example shown in last week’s class as well. He seems to be focusing on natural forces and how one might feel in a space surrounded by these elements over time. Which makes sense when we think about his explanation for this particular artwork. He mentions that the word "Martyr" comes from the Greek word (μάρτυς) which means "witness". This has deep ties with religion as well where books refer to people bearing witness to death and resurrection (you can also see the resemblance to Jesus' crucifixion pose in the image below). The screens were being displayed right across from a baroque organ too, which is pretty on theme I'd say.

In our current time, the media makes us all witnesses to human suffering around the world. I believe that these four screens showcase the human capacity to bear pain in order to remain true to whatever's keeping them alive (the chair, the ropes, maybe their values and beliefs).

I remember seeing a bunch of other versions of the Bakelite Robot online but the version in the MAG had 7 screens that each displayed colourful moving images reminiscent of the Windows Media Player sound visualisations. The “robot” aspect of the work came from the humanoid shape created by the merging of multiple radios. It had a head, a torso, arms, and legs, and the small TV screens were placed into the hollow circular spaces left from the dials removed from the radios.

For me personally, this humanoid presentation was more impactful than seeing a bunch of screens on a wall. Humans tend to anthropomorphise inanimate objects all the time. I believe that having this artwork shaped like a tiny human helped museum-goers feel a deeper connection than they would have felt normally, in the given time and space.

The second example, again in MAG, was the video installation of Bill Viola called “Martyrs”. This particular work was presented in the form of four vertical HD flat-screen monitors next to each other. On each screen, there was a human figure gradually being engulfed in either water, earth, fire, or air. I remember seeing an elemental approach in the example shown in last week’s class as well. He seems to be focusing on natural forces and how one might feel in a space surrounded by these elements over time. Which makes sense when we think about his explanation for this particular artwork. He mentions that the word "Martyr" comes from the Greek word (μάρτυς) which means "witness". This has deep ties with religion as well where books refer to people bearing witness to death and resurrection (you can also see the resemblance to Jesus' crucifixion pose in the image below). The screens were being displayed right across from a baroque organ too, which is pretty on theme I'd say.

In our current time, the media makes us all witnesses to human suffering around the world. I believe that these four screens showcase the human capacity to bear pain in order to remain true to whatever's keeping them alive (the chair, the ropes, maybe their values and beliefs).

-

firving-beck

- Posts: 9

- Joined: Wed Oct 01, 2025 2:26 pm

Re: wk3 10.07/10.09: Digital Image, Time, Space, Interactivity, Narrative

I was particularly struck by two vastly different uses of machine-generated aesthetics to manipulate time, especially distinct from one another since they both work with human source material. The first of which is Rokeby’s San Marco Flow, which captures the temporal element linearly via long exposure. The second piece, MODELL 5, uses granular synthesis to remix footage on a microscopic level. How might time be used to disrupt versus to extend a prior-existing visual narrative?

In San Marco Flow, by tracking human paths, the passage of time is captured in a semi-static (slow motion?) way. The video has a comforting, lulling effect due to the soft light trails and regular pacing. The footage serves as a continuation/extension of the original experience, since it is linear and understandable from the human perspective. Despite being “zoomed out” and capturing less recognizable detail, it feels atmospheric and almost impressionistic, and therefore reads as more universal. Adding to this effect, San Marco Flow speaks to the collective, modeling a group dynamic and larger social region rather than an individual.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=M7tPyB_jEhE

In contrast, MODELL 5 continually remixes the video violently, creating an overwhelming and visceral experience for the viewer. The use of granular synthesis renders footage and expression incomprehensible, leaning into an inhuman perspective. In this case, the typical narrative and understanding is upended – any semblance of recognizable expression or movement is quickly destroyed by remixing. This is despite having a more “personal” and intimate premise, where the viewer is situated in front (and literally surrounded by) a singular human face. Individualism instead serves to alienate the viewer.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ATWljMbvVTg

In San Marco Flow, by tracking human paths, the passage of time is captured in a semi-static (slow motion?) way. The video has a comforting, lulling effect due to the soft light trails and regular pacing. The footage serves as a continuation/extension of the original experience, since it is linear and understandable from the human perspective. Despite being “zoomed out” and capturing less recognizable detail, it feels atmospheric and almost impressionistic, and therefore reads as more universal. Adding to this effect, San Marco Flow speaks to the collective, modeling a group dynamic and larger social region rather than an individual.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=M7tPyB_jEhE

In contrast, MODELL 5 continually remixes the video violently, creating an overwhelming and visceral experience for the viewer. The use of granular synthesis renders footage and expression incomprehensible, leaning into an inhuman perspective. In this case, the typical narrative and understanding is upended – any semblance of recognizable expression or movement is quickly destroyed by remixing. This is despite having a more “personal” and intimate premise, where the viewer is situated in front (and literally surrounded by) a singular human face. Individualism instead serves to alienate the viewer.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ATWljMbvVTg

-

ericmrennie

- Posts: 9

- Joined: Wed Oct 01, 2025 2:33 pm

Re: wk3 10.07/10.09: Digital Image, Time, Space, Interactivity, Narrative

One of the most significant and contemporary qualities of computer-based art is its capacity to directly involve the viewer, granting them an active role in shaping the narrative. Three works that exemplify this idea are Lorna by Lynn Hershman Leeson, As Yet Untitled by Max Dean, and Videoplace by Myron Krueger.

Lorna, a story about an agoraphobic woman, is an interactive piece of video art created for LaserDisc. In this work, the viewer assumes the role of the user, selecting menu options that shape a non-linear narrative. The user can interact with objects in a manner similar to a role-playing game (RPG), effectively choosing their own adventure. By exploring Lorna’s environment, the user develops empathy for her condition, experiencing the constraints and limitations imposed by her apartment. Each viewing of Lorna produces different storylines, ultimately culminating in one of several possible endings: Lorna taking her own life, leaving her apartment for Los Angeles, or destroying her television set (McNeil).

Lynn Hershman Leeson's Lorna (McNeil)

Myron Krueger, a pioneer of augmented reality, created Videoplace in 1975. This interactive installation allows two participants, either in the same room or across the world, to engage directly with the work. When a participant enters the space, their silhouette is projected onto a screen in front of them. By moving their bodies, participants can navigate the screen and manipulate each other’s images through resizing, rotation, color changes, and other transformations. In this way, the participants become active creators of the artwork (Krueger).

Max Krueger's Videoplace (Krueger)

Lastly, As Yet Untitled by Max Dean places the viewer in control of the fate of family photographs. A robotic arm in the piece is programmed to pick up a photograph and present it to the viewer. The robot will then place the photo in a shredder unless the participant places their hands on two cutouts which signals the robot to save it. If no viewer intervenes or if the viewer chooses not to stop the shredding, the photographs are fed into the shredder (Dean).

Max Dean's As Yet Untitled (Dean)

Works Cited

Dean, Max. As Yet Untitled - 1992–1995. n.d. Web. 13 Oct. 2025. https://www.maxdean.ca/19901999/as-yet- ... -1992-1995.

Krueger, Myron. Videoplace. n.d. Web. 13 Oct. 2025. https://aboutmyronkrueger.weebly.com/videoplace.html.

McNeil, Erin. "On Lynn Hershman Leeson’s Lorna." Walker Art Center, 15 July 2016, https://walkerart.org/magazine/lynn_her ... zymandias/

Lorna, a story about an agoraphobic woman, is an interactive piece of video art created for LaserDisc. In this work, the viewer assumes the role of the user, selecting menu options that shape a non-linear narrative. The user can interact with objects in a manner similar to a role-playing game (RPG), effectively choosing their own adventure. By exploring Lorna’s environment, the user develops empathy for her condition, experiencing the constraints and limitations imposed by her apartment. Each viewing of Lorna produces different storylines, ultimately culminating in one of several possible endings: Lorna taking her own life, leaving her apartment for Los Angeles, or destroying her television set (McNeil).

Lynn Hershman Leeson's Lorna (McNeil)

Myron Krueger, a pioneer of augmented reality, created Videoplace in 1975. This interactive installation allows two participants, either in the same room or across the world, to engage directly with the work. When a participant enters the space, their silhouette is projected onto a screen in front of them. By moving their bodies, participants can navigate the screen and manipulate each other’s images through resizing, rotation, color changes, and other transformations. In this way, the participants become active creators of the artwork (Krueger).

Max Krueger's Videoplace (Krueger)

Lastly, As Yet Untitled by Max Dean places the viewer in control of the fate of family photographs. A robotic arm in the piece is programmed to pick up a photograph and present it to the viewer. The robot will then place the photo in a shredder unless the participant places their hands on two cutouts which signals the robot to save it. If no viewer intervenes or if the viewer chooses not to stop the shredding, the photographs are fed into the shredder (Dean).

Max Dean's As Yet Untitled (Dean)

Works Cited

Dean, Max. As Yet Untitled - 1992–1995. n.d. Web. 13 Oct. 2025. https://www.maxdean.ca/19901999/as-yet- ... -1992-1995.

Krueger, Myron. Videoplace. n.d. Web. 13 Oct. 2025. https://aboutmyronkrueger.weebly.com/videoplace.html.

McNeil, Erin. "On Lynn Hershman Leeson’s Lorna." Walker Art Center, 15 July 2016, https://walkerart.org/magazine/lynn_her ... zymandias/

Re: wk3 10.07/10.09: Digital Image, Time, Space, Interactivity, Narrative

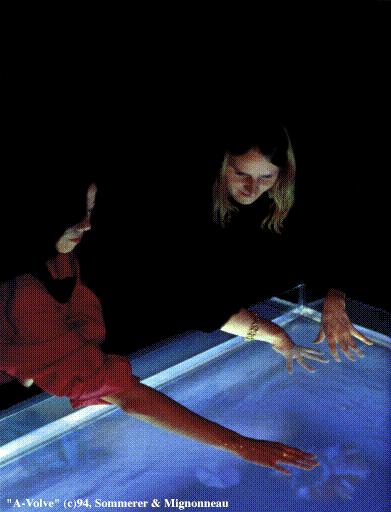

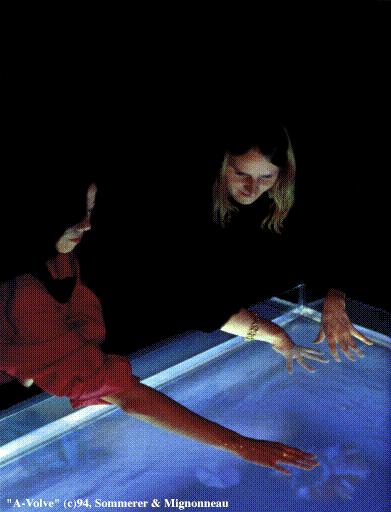

A-volve (1994) by Christa Sommerer and Laurent Mignonneau is an interactive installation that allows visitors to participate in the creation of virtual life forms. Through audience input, these digital organisms come to life, interacting both with viewers and with one another to form an infinite life cycle that reflects human behavior and the principles of evolution.

A-volve (1994) by Christa Sommerer & Laurent Mignonneau

While experiencing A-volve, I was reminded of several other artworks and games that explore artificial ecosystems and the cycles of life. One example is Flow, an artistic video game designed by Jenova Chen and Nicholas Clark, which visualizes the theory of “flow” through a microcosmic aquatic ecosystem where microorganisms evolve by consuming others.

Flow (2006) by Jenova Chen & Nicholas Clark

Another related example is Will Wright’s game Spore, which focuses on evolution as a creative and interactive process. In Spore, the player begins as a single-cell organism and gradually evolves into a complex, intelligent being. Each action taken during the early microbial stage influences how the organism develops in later stages, illustrating how small-scale behaviors shape large-scale evolutionary outcomes.

Spore (2008) by Will Wright / Maxis

In the field of media art, subsequent works that further developed the idea of artificial ecosystems include Ian Cheng’s Emissaries trilogy and BOB (Bag of Beliefs). Cheng’s works use game engines and artificial intelligence to generate virtual worlds that evolve autonomously, without direct human intervention.

Emissaries (2015–2017) by Ian Cheng

Similarly, Haru Ji and Graham Wakefield’s Artificial Nature series creates immersive mixed-reality ecosystems inspired by complex systems theory and biology. These environments are designed to continuously transform and adapt through interactions with their physical and social surroundings.

Artificial Nature (2011–present) by Haru Ji & Graham Wakefield

From A-volve’s audience-generated organisms to Ian Cheng’s AI-driven ecosystems, these works all depict evolving entities that interact with one another and their environments. To me, they embody the essence of media art. Media art is not a static medium; its definition continually shifts alongside the technologies and cultural contexts of its time. Like a living organism, media art itself evolves and transforms. This is precisely what makes it both time-based and interactive by nature.

https://www.spore.com/

https://jenovachen.info/flow

http://www.data-ai.design/2021-2022/art ... ature.html

https://iancheng.com/

https://interface.ufg.ac.at/christa-laurent

A-volve (1994) by Christa Sommerer & Laurent Mignonneau

While experiencing A-volve, I was reminded of several other artworks and games that explore artificial ecosystems and the cycles of life. One example is Flow, an artistic video game designed by Jenova Chen and Nicholas Clark, which visualizes the theory of “flow” through a microcosmic aquatic ecosystem where microorganisms evolve by consuming others.

Flow (2006) by Jenova Chen & Nicholas Clark

Another related example is Will Wright’s game Spore, which focuses on evolution as a creative and interactive process. In Spore, the player begins as a single-cell organism and gradually evolves into a complex, intelligent being. Each action taken during the early microbial stage influences how the organism develops in later stages, illustrating how small-scale behaviors shape large-scale evolutionary outcomes.

Spore (2008) by Will Wright / Maxis

In the field of media art, subsequent works that further developed the idea of artificial ecosystems include Ian Cheng’s Emissaries trilogy and BOB (Bag of Beliefs). Cheng’s works use game engines and artificial intelligence to generate virtual worlds that evolve autonomously, without direct human intervention.

Emissaries (2015–2017) by Ian Cheng

Similarly, Haru Ji and Graham Wakefield’s Artificial Nature series creates immersive mixed-reality ecosystems inspired by complex systems theory and biology. These environments are designed to continuously transform and adapt through interactions with their physical and social surroundings.

Artificial Nature (2011–present) by Haru Ji & Graham Wakefield

From A-volve’s audience-generated organisms to Ian Cheng’s AI-driven ecosystems, these works all depict evolving entities that interact with one another and their environments. To me, they embody the essence of media art. Media art is not a static medium; its definition continually shifts alongside the technologies and cultural contexts of its time. Like a living organism, media art itself evolves and transforms. This is precisely what makes it both time-based and interactive by nature.

https://www.spore.com/

https://jenovachen.info/flow

http://www.data-ai.design/2021-2022/art ... ature.html

https://iancheng.com/

https://interface.ufg.ac.at/christa-laurent

Last edited by hyuncho on Fri Dec 12, 2025 1:26 pm, edited 1 time in total.

Re: wk3 10.07/10.09: Digital Image, Time, Space, Interactivity, Narrative

Time-based art installations are one of the most interesting fields in contemporary art. Thanks to technology, artists can now manipulate and create beyond traditional concepts. Today, with advances in audio, video, and real-time data processing, artworks can be transformed and made to feel “alive.”

I am especially interested in “living sculptures” or installations inspired by nature that use principles of biomimesis. One of the most relevant artists in this field for me is Neri Oxman, who has been working with insects and living materials to create art and design.

Based on this week’s resources, I selected the following works:

1. David Rokeby – San Marco Flow (Generative Video Installation, 2004)

San Marco Flow was an installation in Piazza San Marco in Venice, where movement and time were central elements. As people walked or moved through the space, the installation visualized their presence, leaving a kind of trace behind them that showed their past pathways. This generated the idea that as we move forward, we always leave traces behind.

What I found most interesting is that without movement, there is no image — elements that do not move remain invisible to the program.

The key concepts I identify are:

a) time and the traces we leave behind;

b) movement as evidence of life; and

c) data transformation to reveal the invisible.

2. Jim Campbell – Data Transformation 3 (2017)

Jim Campbell holds a B.S. in Electrical Engineering and Mathematics from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. His work has been exhibited internationally in institutions such as the Whitney Museum of American Art (New York) and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, among others.

In this work, he transforms visual information by adding noise or effects that create the illusion of low resolution. The piece uses electronic devices such as LEDs to display images in a way that merges abstraction and data representation. As Campbell explains about Data Transformation 3 (2017):

“By reducing the resolution of the color side of the image, the two sides present similar amounts of information, with each side representing the data in a different way.”

What attracted my attention was how the transformation of movement captured in the videos completes the experience. The changing images make me reinterpret the same “reality” by focusing on different aspects of it.

The key elements I identify are:

a) visuals based on simple rules that generate complex results;

b) shifting focus to different aspects of the same information; and

c) inviting the viewer to change perspective — to “see with new eyes.”

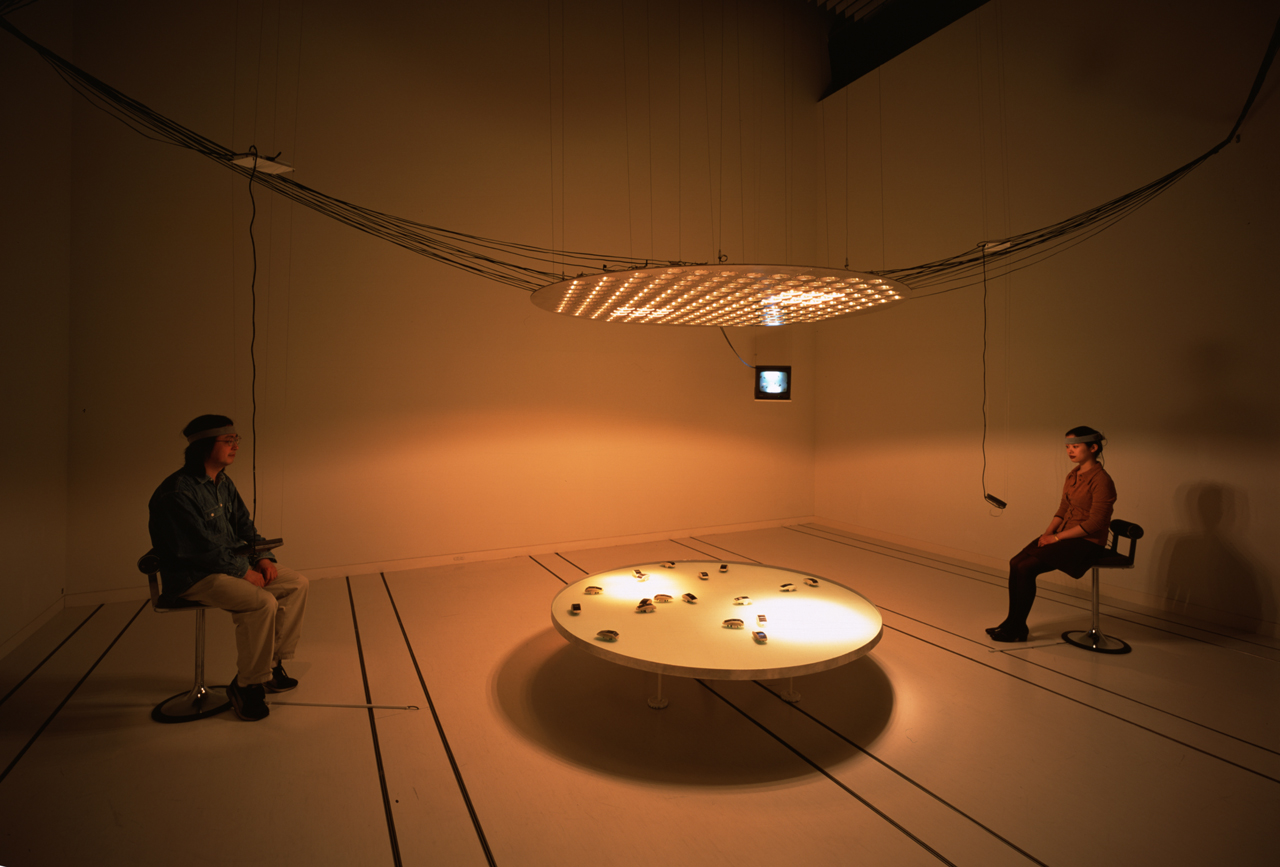

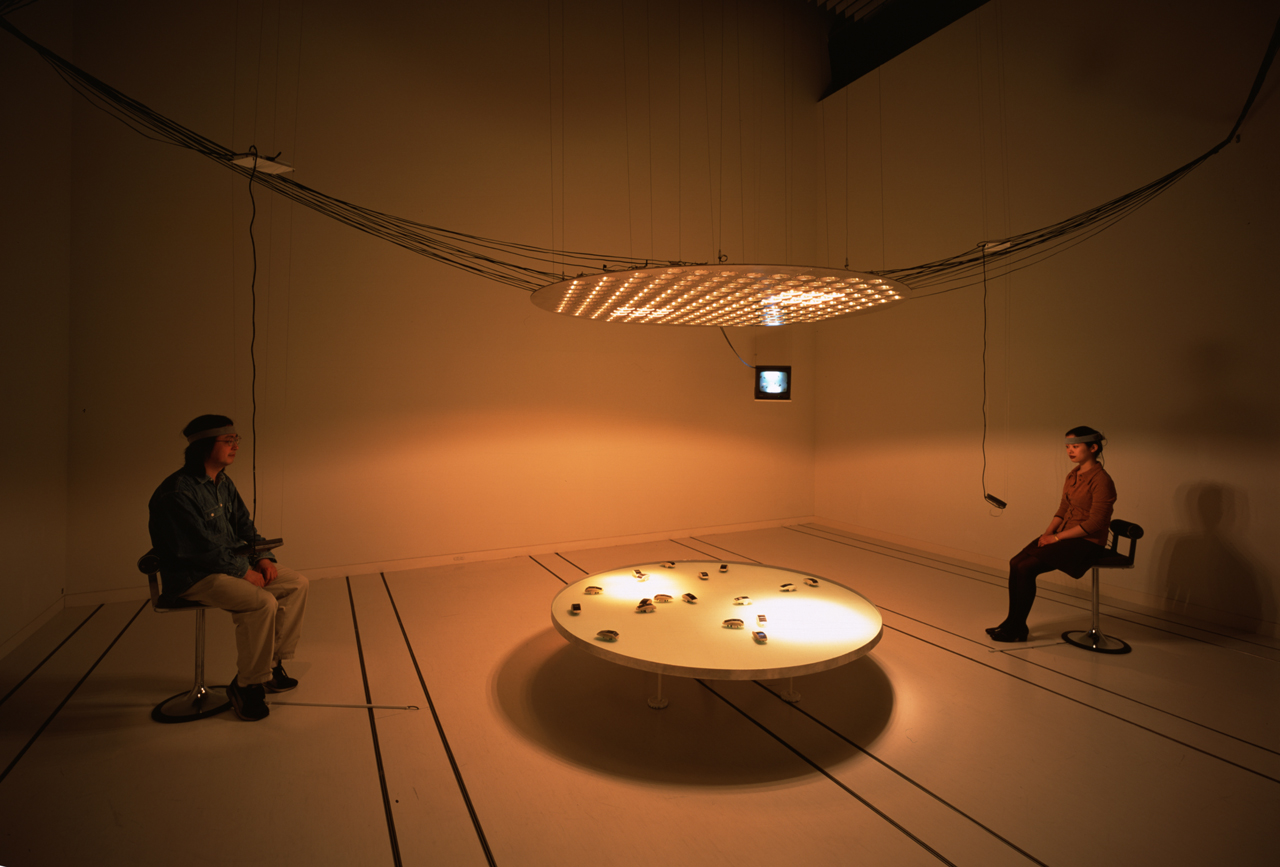

3. Ulrike Gabriel – terrain_02 (1997)

Ulrike Gabriel explores human reality through robotics, virtual reality (VR), installations, performative formats, and painting. In terrain_02, she worked with biodata and light-responsive devices.

Two participants sit in a nonverbal dialogue facing each other at a round table. They are connected via EEG interfaces to a system of solar-powered robots. Their brainwaves are measured, analyzed, and compared. The ratio between both frequencies is projected onto the robots through changing light intensities—from above using lamps and from below using electroluminescent sheets. The light controls the speed and behavior of the robots, activating or deactivating different areas of the terrain. Depending on the participants’ relationship and their inner responses to each other, unique motion patterns emerge.

I selected this piece because I am interested in biodata as well. It is fascinating to understand the work as one that evolves over time, depending on the dialogue between the participants. This dialogue is unique, as is their relationship. For me, it is important to see the interaction between the different elements: the display of small robots that begin to move because of light creates an internal narrative. Light induces movement and, as a consequence, sets the conditions for life.

The key concepts I identify are:

a) light as a source of life;

b) biodata as a tool to reveal relationships between humans and non-humans.

I am especially interested in “living sculptures” or installations inspired by nature that use principles of biomimesis. One of the most relevant artists in this field for me is Neri Oxman, who has been working with insects and living materials to create art and design.

Based on this week’s resources, I selected the following works:

1. David Rokeby – San Marco Flow (Generative Video Installation, 2004)

San Marco Flow was an installation in Piazza San Marco in Venice, where movement and time were central elements. As people walked or moved through the space, the installation visualized their presence, leaving a kind of trace behind them that showed their past pathways. This generated the idea that as we move forward, we always leave traces behind.

What I found most interesting is that without movement, there is no image — elements that do not move remain invisible to the program.

The key concepts I identify are:

a) time and the traces we leave behind;

b) movement as evidence of life; and

c) data transformation to reveal the invisible.

2. Jim Campbell – Data Transformation 3 (2017)

Jim Campbell holds a B.S. in Electrical Engineering and Mathematics from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. His work has been exhibited internationally in institutions such as the Whitney Museum of American Art (New York) and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, among others.

In this work, he transforms visual information by adding noise or effects that create the illusion of low resolution. The piece uses electronic devices such as LEDs to display images in a way that merges abstraction and data representation. As Campbell explains about Data Transformation 3 (2017):

“By reducing the resolution of the color side of the image, the two sides present similar amounts of information, with each side representing the data in a different way.”

What attracted my attention was how the transformation of movement captured in the videos completes the experience. The changing images make me reinterpret the same “reality” by focusing on different aspects of it.

The key elements I identify are:

a) visuals based on simple rules that generate complex results;

b) shifting focus to different aspects of the same information; and

c) inviting the viewer to change perspective — to “see with new eyes.”

3. Ulrike Gabriel – terrain_02 (1997)

Ulrike Gabriel explores human reality through robotics, virtual reality (VR), installations, performative formats, and painting. In terrain_02, she worked with biodata and light-responsive devices.

Two participants sit in a nonverbal dialogue facing each other at a round table. They are connected via EEG interfaces to a system of solar-powered robots. Their brainwaves are measured, analyzed, and compared. The ratio between both frequencies is projected onto the robots through changing light intensities—from above using lamps and from below using electroluminescent sheets. The light controls the speed and behavior of the robots, activating or deactivating different areas of the terrain. Depending on the participants’ relationship and their inner responses to each other, unique motion patterns emerge.

I selected this piece because I am interested in biodata as well. It is fascinating to understand the work as one that evolves over time, depending on the dialogue between the participants. This dialogue is unique, as is their relationship. For me, it is important to see the interaction between the different elements: the display of small robots that begin to move because of light creates an internal narrative. Light induces movement and, as a consequence, sets the conditions for life.

The key concepts I identify are:

a) light as a source of life;

b) biodata as a tool to reveal relationships between humans and non-humans.