wk5 10.21/10.23 Systems Art, Generative Art, Algorithmic Art, Bio Art, Biometrics, Bio Data

Give a response to any of the material covered in this week's presentations

wk5 10.21/10.23 Systems Art, Generative Art, Algorithmic Art, Bio Art, Biometrics, Bio Data

-

jintongyang

- Posts: 5

- Joined: Wed Oct 01, 2025 2:38 pm

Re: wk5 10.21/10.23 Systems Art, Generative Art, Algorithmic Art, Bio Art, Biometrics, Bio Data

Human agency versus mechanical performance has long been a continuous discussion in both art and science, and it remains a source of inspiration for many media art practices. I am particularly drawn to the question of how natural life forms (patterns, unpredictability, and emotional depth) can be transformed, recreated or generated through mechanical and computational systems, and what this means for our understanding of creativity, evolution, and sentience.

In early generative art, the artist’s role was still close to that of a programmer or mathematician: the rules were written by hand, diagrams were deterministic, and the system’s autonomy was limited. Yet, even at this stage, artists were already searching for ways to let the machine become a partner in creation rather than a tool. In the 1960s, Gottfried Jäger’s concept of Generative Photography proposed that artists could construct “aesthetic states” through mechanical and chemical processes rather than capturing reality, echoing Max Bense’s Generative Aesthetics. Decades later, digital artists expanded this logic into algorithmic and data-driven systems that could not only execute rules but also adapt, learn, and evolve.

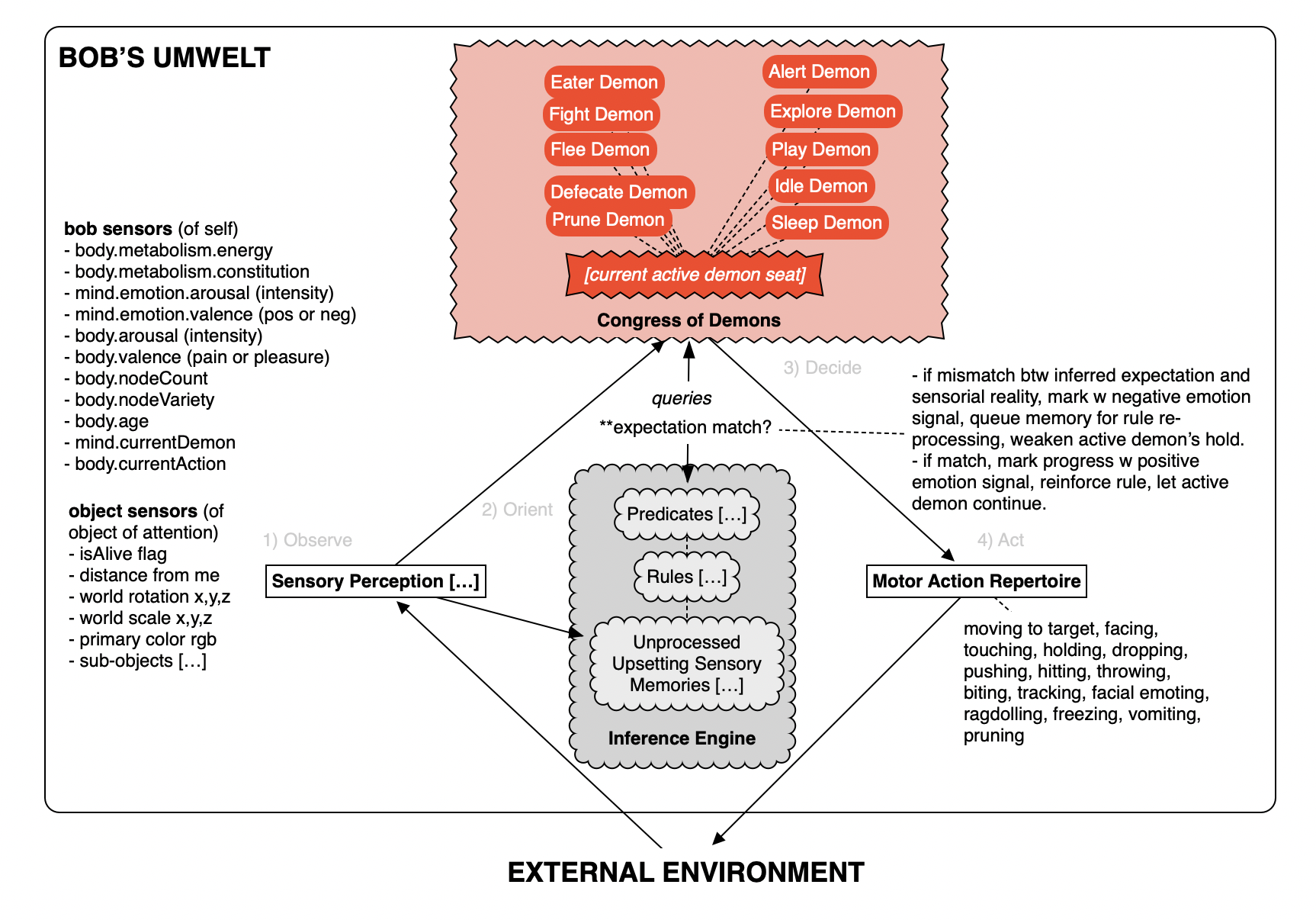

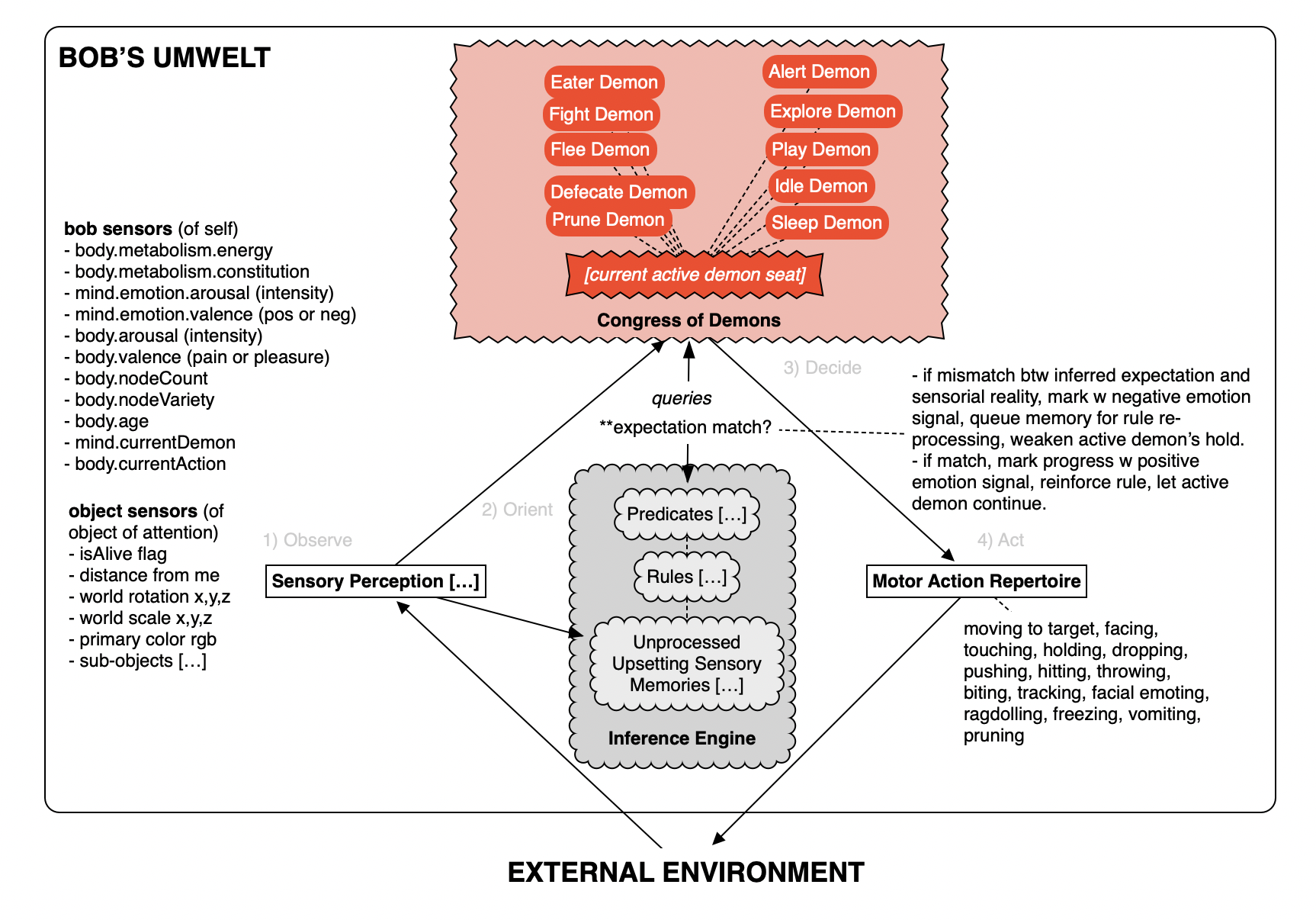

The notion of evolution, once rooted in biology, now extends into computation. For machines, to evolve means to learn, to adjust internal states in response to feedback. In BOB (Bag of Beliefs) (2018) (Fig.1), artist Ian Cheng creates a hybrid virtual life form governed by a set of competing “demons,” each responsible for different behaviors such as feeding, exploring, fleeing, or resting. What fascinates me is that BOB does not simply execute code; it continuously updates its beliefs through interaction with real humans. Cheng does not sculpt BOB’s form; he sculpts the conditions for its learning. In doing so, he transforms code into ecology, suggesting that human and machine now coevolve within the same cognitive environment.

Fig.1. Ian Cheng, BOB (Bag of Beliefs) (2018)

This theme of coevolution between human and nonhuman entities reappears in Eduardo Kac’s Natural History of the Enigma (2003) (Fig.2) and Sougwen Chung’s Realm of Silk (2023) (Fig.3). In Edunia, Kac embedded a fragment of his own DNA into a petunia, creating a living hybrid whose red veins symbolically carry his blood. Meanwhile, in Realm of Silk, Chung performs with four AI-powered robotic arms that move and paint alongside her on stage, enacting a choreography of shared authorship. Both artists challenge us to reconsider where “the human” ends and “the natural” begins, suggesting that identity is not fixed but constantly reassembled across biological and technological boundaries.

Fig.2. Eduardo Kac, Natural History of the Enigma (2003)

Fig.3. Sougwen Chung, Realm of Silk (2023)

Yet as biological data becomes manipulable, questions of privacy and ethics evoke. By collecting discarded objects such as gum, hair, or cigarette butts from public spaces and extracting DNA to 3D-print faces, Heather Dewey-Hagborg’s Stranger Visions (2013) (Fig.4) exposes how data has become the body itself. Are what we leave behind ever truly gone? What used to be invisible biological traces have become readable codes, potentially reconstructing our likeness without consent. In the age of machine learning, where every fragment of information becomes training material, we might ask what happens when our biological remains begin to “learn us” back and become deadly weapons against ourselves.

Fig.4. Heather Dewey-Hagborg, Stranger Visions (2013)

In a word, I believe that no matter how we coexist and coevolve with both nature and machines in the future, we must continue to reflect on our connections, to experiment with empathy and respect, and to seek a balance that sustains our shared well-being.

In early generative art, the artist’s role was still close to that of a programmer or mathematician: the rules were written by hand, diagrams were deterministic, and the system’s autonomy was limited. Yet, even at this stage, artists were already searching for ways to let the machine become a partner in creation rather than a tool. In the 1960s, Gottfried Jäger’s concept of Generative Photography proposed that artists could construct “aesthetic states” through mechanical and chemical processes rather than capturing reality, echoing Max Bense’s Generative Aesthetics. Decades later, digital artists expanded this logic into algorithmic and data-driven systems that could not only execute rules but also adapt, learn, and evolve.

The notion of evolution, once rooted in biology, now extends into computation. For machines, to evolve means to learn, to adjust internal states in response to feedback. In BOB (Bag of Beliefs) (2018) (Fig.1), artist Ian Cheng creates a hybrid virtual life form governed by a set of competing “demons,” each responsible for different behaviors such as feeding, exploring, fleeing, or resting. What fascinates me is that BOB does not simply execute code; it continuously updates its beliefs through interaction with real humans. Cheng does not sculpt BOB’s form; he sculpts the conditions for its learning. In doing so, he transforms code into ecology, suggesting that human and machine now coevolve within the same cognitive environment.

Fig.1. Ian Cheng, BOB (Bag of Beliefs) (2018)

This theme of coevolution between human and nonhuman entities reappears in Eduardo Kac’s Natural History of the Enigma (2003) (Fig.2) and Sougwen Chung’s Realm of Silk (2023) (Fig.3). In Edunia, Kac embedded a fragment of his own DNA into a petunia, creating a living hybrid whose red veins symbolically carry his blood. Meanwhile, in Realm of Silk, Chung performs with four AI-powered robotic arms that move and paint alongside her on stage, enacting a choreography of shared authorship. Both artists challenge us to reconsider where “the human” ends and “the natural” begins, suggesting that identity is not fixed but constantly reassembled across biological and technological boundaries.

Fig.2. Eduardo Kac, Natural History of the Enigma (2003)

Fig.3. Sougwen Chung, Realm of Silk (2023)

Yet as biological data becomes manipulable, questions of privacy and ethics evoke. By collecting discarded objects such as gum, hair, or cigarette butts from public spaces and extracting DNA to 3D-print faces, Heather Dewey-Hagborg’s Stranger Visions (2013) (Fig.4) exposes how data has become the body itself. Are what we leave behind ever truly gone? What used to be invisible biological traces have become readable codes, potentially reconstructing our likeness without consent. In the age of machine learning, where every fragment of information becomes training material, we might ask what happens when our biological remains begin to “learn us” back and become deadly weapons against ourselves.

Fig.4. Heather Dewey-Hagborg, Stranger Visions (2013)

In a word, I believe that no matter how we coexist and coevolve with both nature and machines in the future, we must continue to reflect on our connections, to experiment with empathy and respect, and to seek a balance that sustains our shared well-being.

-

ericmrennie

- Posts: 5

- Joined: Wed Oct 01, 2025 2:33 pm

Re: wk5 10.21/10.23 Systems Art, Generative Art, Algorithmic Art, Bio Art, Biometrics, Bio Data

Generative art is defined as any art that uses systems, such as software, natural language rules, machines, or other procedural inventions, which are used with some autonomy in order to create works of art (Galanter). These artworks balance the compressibility of order—such as symmetry and tiling—and the incompressibility of disorder—such as randomization—ultimately displaying effective complexity. The practice of generative art gained momentum in the late 1960s and early 1970s, with artists such as Vera Molnár, Gottfried Jäger, and Lars Fredrikson.

Vera Mólnar was one of the first women to use computers in her fine art practice, and is considered a pioneer of the generative art aspect of computer art (“Vera Mólnar). She created one of her famous works, Interruptions, between 1968 and 1969. In this series, she started with a grid covered in straight lines of similar lengths, and then randomized the rotation and erasure of certain sections, leaving large voids in the work. In this piece, Mólnar applies chaos – a computer algorithm – to a regular structure, the grid.

Interruptions by Vera Mólnar

https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O119 ... lnar-vera/

Not all artists used computers to create generative art though, such as Gottfried Jäger. In his piece, Pinhole Structures, he used the camera obscura, or pinhole camera, to produce geometric patterns. By using multiple lenses on a camera, Jäger was able to perform displacement and translation of outer light onto the film (“Gottfried Jäger). He created pinhole patterns on the lenses which were moved in order to create geometric patterns.

Pinhole Structures by Gottfried Jäger

https://in.pinterest.com/ideas/

In addition to computers and film, another technology that was used in the 1960s to create generative art was the fax machine or copy printer. Lars Fredrikson, who became interested in art while simultaneously studying chemistry and electronics, used this medium in his practice. In his fax drawings piece, Fredrikson used radio waves in order to create images with a fax machine that he converted into a drawing machine (“Lars Fredrickson”).

fax drawings by Lars Fredrikson

http://www.insituparis.fr/fr/artistes/p ... state-lars

With the rapid emergence of new technologies in the 1960s and 1970s, it’s no wonder artists began to see these mediums as untapped tools for creation. Because these technologies were not entirely extensions of the artist, generative art introduced elements of randomness, uncertainty, and temporality into the creative process. In doing so, technology existed somewhere between a tool for the artist and a collaborator.

Works Cited

Galanter, Philip. What Is Generative Art? Complexity Theory as a Context for Art Theory. 2003. New York University, Interactive Telecommunications Program, pdf file. https://www.philipgalanter.com/download ... _paper.pdf. Accessed 27 Oct. 2025. Philip Galanter+1

“Gottfried Jäger.” Sous Les Étoiles Gallery, 17 May 2018. https://www.souslesetoilesgallery.net/e ... 20patterns. Accessed 27 Oct. 2025. Sous Les Etoiles Gallery

“Lars Fredrikson.” Monoskop, last edited 30 May 2025. https://monoskop.org/Lars_Fredrikson. Accessed 27 Oct. 2025.

“Vera Molnár.” Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia. Wikimedia Foundation, last edited 2 Sept. 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vera_Moln%C3%A1r. Accessed 27 Oct. 2025. Wikipedia

Vera Mólnar was one of the first women to use computers in her fine art practice, and is considered a pioneer of the generative art aspect of computer art (“Vera Mólnar). She created one of her famous works, Interruptions, between 1968 and 1969. In this series, she started with a grid covered in straight lines of similar lengths, and then randomized the rotation and erasure of certain sections, leaving large voids in the work. In this piece, Mólnar applies chaos – a computer algorithm – to a regular structure, the grid.

Interruptions by Vera Mólnar

https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O119 ... lnar-vera/

Not all artists used computers to create generative art though, such as Gottfried Jäger. In his piece, Pinhole Structures, he used the camera obscura, or pinhole camera, to produce geometric patterns. By using multiple lenses on a camera, Jäger was able to perform displacement and translation of outer light onto the film (“Gottfried Jäger). He created pinhole patterns on the lenses which were moved in order to create geometric patterns.

Pinhole Structures by Gottfried Jäger

https://in.pinterest.com/ideas/

In addition to computers and film, another technology that was used in the 1960s to create generative art was the fax machine or copy printer. Lars Fredrikson, who became interested in art while simultaneously studying chemistry and electronics, used this medium in his practice. In his fax drawings piece, Fredrikson used radio waves in order to create images with a fax machine that he converted into a drawing machine (“Lars Fredrickson”).

fax drawings by Lars Fredrikson

http://www.insituparis.fr/fr/artistes/p ... state-lars

With the rapid emergence of new technologies in the 1960s and 1970s, it’s no wonder artists began to see these mediums as untapped tools for creation. Because these technologies were not entirely extensions of the artist, generative art introduced elements of randomness, uncertainty, and temporality into the creative process. In doing so, technology existed somewhere between a tool for the artist and a collaborator.

Works Cited

Galanter, Philip. What Is Generative Art? Complexity Theory as a Context for Art Theory. 2003. New York University, Interactive Telecommunications Program, pdf file. https://www.philipgalanter.com/download ... _paper.pdf. Accessed 27 Oct. 2025. Philip Galanter+1

“Gottfried Jäger.” Sous Les Étoiles Gallery, 17 May 2018. https://www.souslesetoilesgallery.net/e ... 20patterns. Accessed 27 Oct. 2025. Sous Les Etoiles Gallery

“Lars Fredrikson.” Monoskop, last edited 30 May 2025. https://monoskop.org/Lars_Fredrikson. Accessed 27 Oct. 2025.

“Vera Molnár.” Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia. Wikimedia Foundation, last edited 2 Sept. 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vera_Moln%C3%A1r. Accessed 27 Oct. 2025. Wikipedia

-

jcrescenzo

- Posts: 4

- Joined: Wed Oct 01, 2025 2:17 pm

Re: wk5 10.21/10.23 Systems Art, Generative Art, Algorithmic Art, Bio Art, Biometrics, Bio Data

What is Generative Art: A Review of Phillip Galanter’s Essay

The question of what is generative is a loaded question but by looking at the art piece “A Becoming Resemblance” we can provide a clear definition of Galanter’s definition

Glanter argues that “the defining aspect of generative art seems to be the use of an autonomous system for art making.” In this sense the artist gives up some partial process of art-making to a generative system.

In the case of Heather Dewey-Hagborg, she uses Chelsea Manning’s DNA to reproduce computer generated images of her face. In this case, DNA is the constructor of the 3D model, determining the structure of Manning's head and face. Manning leaked to journalist evidence of the US government's illegal surveillance of its population.

But this is not a linear process but a complex system, where localized components interact with each other and lead to “self organizing systems.” Complex systems operate on a continuum, a mixture of highly ordered and highly disordered.

Artist Dewey-Hagborg points out that the use of Manning’s DNA led to 30 different versions of his 3D constructed head due to the diversity of Chelsea’s genome, “a diversity in which that same DNA data can be read.” The use of Manning’s DNA structure creates a human face rather than the face of a giraffe. It is produced by “algorithmically reading Chelsea’s DNA data” but allows for variation (CNN). The generative art process is a chaotic system rather than a random one.

With generative art, we must understand that there is a balance between “a highly ordered system and a highly disordered aesthetic experience.” Pure randomness has no structure, but purely deterministic generative systems create redundancy.

All that said, Galanter points out that generative art need not be highly technological but generative

Dewey-Hagborg’s “A Becoming Resemblance” is a piece which uses a generative process by means of the computer but this does not have to be the case. The Dada Art movement introduced randomization into the art process, such as cutting up paper and tossing it over their shoulder, where it would randomly stick to the canvas.

https://edition.cnn.com/style/article/c ... ey-hagborg

The question of what is generative is a loaded question but by looking at the art piece “A Becoming Resemblance” we can provide a clear definition of Galanter’s definition

Glanter argues that “the defining aspect of generative art seems to be the use of an autonomous system for art making.” In this sense the artist gives up some partial process of art-making to a generative system.

In the case of Heather Dewey-Hagborg, she uses Chelsea Manning’s DNA to reproduce computer generated images of her face. In this case, DNA is the constructor of the 3D model, determining the structure of Manning's head and face. Manning leaked to journalist evidence of the US government's illegal surveillance of its population.

But this is not a linear process but a complex system, where localized components interact with each other and lead to “self organizing systems.” Complex systems operate on a continuum, a mixture of highly ordered and highly disordered.

Artist Dewey-Hagborg points out that the use of Manning’s DNA led to 30 different versions of his 3D constructed head due to the diversity of Chelsea’s genome, “a diversity in which that same DNA data can be read.” The use of Manning’s DNA structure creates a human face rather than the face of a giraffe. It is produced by “algorithmically reading Chelsea’s DNA data” but allows for variation (CNN). The generative art process is a chaotic system rather than a random one.

With generative art, we must understand that there is a balance between “a highly ordered system and a highly disordered aesthetic experience.” Pure randomness has no structure, but purely deterministic generative systems create redundancy.

All that said, Galanter points out that generative art need not be highly technological but generative

Dewey-Hagborg’s “A Becoming Resemblance” is a piece which uses a generative process by means of the computer but this does not have to be the case. The Dada Art movement introduced randomization into the art process, such as cutting up paper and tossing it over their shoulder, where it would randomly stick to the canvas.

https://edition.cnn.com/style/article/c ... ey-hagborg

Re: wk5 10.21/10.23 Systems Art, Generative Art, Algorithmic Art, Bio Art, Biometrics, Bio Data

This week I’ll discuss three projects that manifest different ways of constructing speculative “lives” under the critical inquiry : What does life consist of?

PlaSphere offers one of the most straightforward answers: life is constructed by the surrounding environment and materials, and it evolves as the ecological environment changes. This audiovisual installation speculates on how new forms of life emerge when human-made materials, like plastic, cans, cigarettes, become part of the natural cycles. The specific location of South Korean islands and coastal regions offer the real ecological system for the speculative discussion. The life training started from real-life plastiglomerate photos, then using data augmentation to create more data for the following LoRA imagery training. Eventually, get the video composition of local creatures that combines local organic & non-organic materials and displays the works as holograms.

Move 36 bridges the conversation between biological material and artificial cognition. Named after the decisive move made by the AI Deep Blue that defeated world chess champion Garry Kasparov, the work interrogates the intersection of biological evolution, machine intelligence, and symbolic thought. At the center of the project lies the creation of a transgenic organism carrying a “Cartesian gene”—a synthetic DNA sequence encoding the phrase “Let us make man in our image, after our likeness.” Through this gesture, Kac collapses distinctions between code, language, and life, suggesting that the essence of being may reside not only in organic material but also in information and meaning. The “Cartesian gene” thus becomes a poetic and philosophical link between the Enlightenment ideal of rational selfhood and the posthuman condition in which thought and biology, machine and organism, continuously co-evolve.

BOB (Bags of Beliefs) then shifts the focus from physical or biological foundations to sentience, personality, and cognition. Here, life is defined not by material bodies but by awareness, belief, and purpose. The “demons” in BOB’s world are entities driven by their internal goals, acting and reacting to one another and their surroundings through sensors of self and object. Artist Ian Cheng presents an especially intriguing perspective: he doesn’t treat these basic demons as independent, self-conscious beings but as components of a larger meta-demon. In this view, humans are the only species capable of summoning and sustaining such a meta-entity—a collective mind that distinguishes our form of life from others.

PlaSphere offers one of the most straightforward answers: life is constructed by the surrounding environment and materials, and it evolves as the ecological environment changes. This audiovisual installation speculates on how new forms of life emerge when human-made materials, like plastic, cans, cigarettes, become part of the natural cycles. The specific location of South Korean islands and coastal regions offer the real ecological system for the speculative discussion. The life training started from real-life plastiglomerate photos, then using data augmentation to create more data for the following LoRA imagery training. Eventually, get the video composition of local creatures that combines local organic & non-organic materials and displays the works as holograms.

Move 36 bridges the conversation between biological material and artificial cognition. Named after the decisive move made by the AI Deep Blue that defeated world chess champion Garry Kasparov, the work interrogates the intersection of biological evolution, machine intelligence, and symbolic thought. At the center of the project lies the creation of a transgenic organism carrying a “Cartesian gene”—a synthetic DNA sequence encoding the phrase “Let us make man in our image, after our likeness.” Through this gesture, Kac collapses distinctions between code, language, and life, suggesting that the essence of being may reside not only in organic material but also in information and meaning. The “Cartesian gene” thus becomes a poetic and philosophical link between the Enlightenment ideal of rational selfhood and the posthuman condition in which thought and biology, machine and organism, continuously co-evolve.

BOB (Bags of Beliefs) then shifts the focus from physical or biological foundations to sentience, personality, and cognition. Here, life is defined not by material bodies but by awareness, belief, and purpose. The “demons” in BOB’s world are entities driven by their internal goals, acting and reacting to one another and their surroundings through sensors of self and object. Artist Ian Cheng presents an especially intriguing perspective: he doesn’t treat these basic demons as independent, self-conscious beings but as components of a larger meta-demon. In this view, humans are the only species capable of summoning and sustaining such a meta-entity—a collective mind that distinguishes our form of life from others.

Re: wk5 10.21/10.23 Systems Art, Generative Art, Algorithmic Art, Bio Art, Biometrics, Bio Data

"Art and Data Team Up Against Climate Change" --- by Annabel Keenan

After reading "Art and Data Team Up Against Climate Change," I began to think more deeply about how biological and data-driven artworks can reshape our understanding of life systems and human relationships with the environment.

For example, the digital time-lapse created by ScanLAB Projects shows a cactus slowly collapsing in the Sonoran Desert. The work doesn’t dramatize the tragedy but visualizes real biological data—the plant’s shrinking volume, its changing texture, its dying motion. This transformation of bio data into a time-based visual form made me realize that data itself can carry a kind of living rhythm, almost like a biological heartbeat recorded through technology. It reminds me of how biometric sensors capture human pulse or breathing. The only difference in things here is that the cactus becomes the body. I also found Janet Echelman’s “Remembering the Future” inspiring. She turns climate data into woven fiber forms that respond to physical space and audience movement. This combination of materiality and data feels similar to how biometrics work—translating invisible biological or environmental changes into something we can see and even feel. These works make me think that Bio Art and Bio Data art are not about “nature vs. technology,” but about finding new languages to translate living systems. From my own perspective as someone working in sound and interactive media, I’m particularly interested in how bio data could be transformed into sound. For instance, using real-time data from heart rate, skin conductivity, or brainwaves to modulate pitch, rhythm, or spatial sound fields. This kind of system would allow the listener to “hear” biological processes, turning the body or an ecosystem into an instrument. I believe that in sound art, bio data can act as a bridge between the physical and emotional dimensions of experience

After reading "Art and Data Team Up Against Climate Change," I began to think more deeply about how biological and data-driven artworks can reshape our understanding of life systems and human relationships with the environment.

For example, the digital time-lapse created by ScanLAB Projects shows a cactus slowly collapsing in the Sonoran Desert. The work doesn’t dramatize the tragedy but visualizes real biological data—the plant’s shrinking volume, its changing texture, its dying motion. This transformation of bio data into a time-based visual form made me realize that data itself can carry a kind of living rhythm, almost like a biological heartbeat recorded through technology. It reminds me of how biometric sensors capture human pulse or breathing. The only difference in things here is that the cactus becomes the body. I also found Janet Echelman’s “Remembering the Future” inspiring. She turns climate data into woven fiber forms that respond to physical space and audience movement. This combination of materiality and data feels similar to how biometrics work—translating invisible biological or environmental changes into something we can see and even feel. These works make me think that Bio Art and Bio Data art are not about “nature vs. technology,” but about finding new languages to translate living systems. From my own perspective as someone working in sound and interactive media, I’m particularly interested in how bio data could be transformed into sound. For instance, using real-time data from heart rate, skin conductivity, or brainwaves to modulate pitch, rhythm, or spatial sound fields. This kind of system would allow the listener to “hear” biological processes, turning the body or an ecosystem into an instrument. I believe that in sound art, bio data can act as a bridge between the physical and emotional dimensions of experience