Artificial intelligence has made significant progress through two key deep learning frameworks: Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) and Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs). Convolutional neural networks stand out from other neural networks due to their strong performance with image, speech, or audio inputs. These networks changed computer vision by automating what was once a slow manual task. Before CNNs, people used tedious feature-extraction methods to detect objects in images. Now, convolutional neural networks offer a more efficient way to classify images and recognize objects. They use concepts from linear algebra, particularly matrix multiplication, to spot patterns within an image. CNNs operate by processing images through layers of filters that gradually identify features, starting with simple edges in the early layers and moving on to complex objects like faces or vehicles in the deeper layers.

While CNNs excel at understanding existing images, GANs introduced something revolutionary: the ability for machines to create entirely new content. A generative adversarial network (GAN) is a type of machine learning framework and a key approach for generating artificial intelligence. The concept was developed by Ian Goodfellow and his colleagues in June 2014. The architecture works through a competitive process. In a GAN, two neural networks compete with each other in a zero-sum game, where one agent's gain is another agent's loss. Given a training set, this technique learns to generate new data with the same statistics as the training set. The generator network tries to create fake data while the discriminator network attempts to distinguish real data from fakes. Through this adversarial training, both networks improve until the generator produces remarkably realistic outputs.

These two architectures play different but important roles in AI systems, and they are often used together. A generative adversarial network is a deep learning setup that trains two neural networks to compete against each other. This competition helps generate more realistic new data from a specific training dataset. For example, you can create new images from an existing image database or compose original music from a collection of songs. AWS CNNs often act as the backbone within GAN architectures. They commonly work as the discriminator network, which assesses the authenticity of images. As the CNN processes information, it develops a hierarchical structure. The later layers can analyze the pixels within the receptive fields of earlier layers. This makes CNNs especially suited for the discriminator's job of spotting subtle differences between real and generated images. This combination has enabled various applications, from creating lifelike faces to generating synthetic medical images for training other AI systems.

The practical uses of both architectures span many industries. CNNs drive autonomous vehicles, medical diagnostic imaging, facial recognition systems, and content moderation on social media platforms. GANs generate realistic images from text prompts or by modifying existing images. They help create immersive visual experiences in video games and digital entertainment. GANs can also edit images, such as changing a low-resolution image to high resolution or transforming a black-and-white image to color. Additionally, generative models can assist with data augmentation by creating synthetic data that mimics real-world data. This is extremely helpful when training data is limited or sensitive. Together, CNNs and GANs showcase the two main functions of modern AI: understanding the world through perception and generating new content.

References

IBM. "What are Convolutional Neural Networks?" https://www.ibm.com/think/topics/convol ... l-networks

Wikipedia. "Generative adversarial network." https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Generativ ... al_network

Amazon Web Services. "What is a GAN? - Generative Adversarial Networks Explained." https://aws.amazon.com/what-is/gan/

wk8 11.11/11.13: Artificial Neural Networks | CNN | Style Transfer, Artificial Intelligence

-

lpfreiburg

- Posts: 10

- Joined: Wed Oct 01, 2025 2:20 pm

-

lucianparisi

- Posts: 9

- Joined: Thu Sep 26, 2024 2:16 pm

Re: wk8 11.11/11.13: Artificial Neural Networks | CNN | Style Transfer, Artificial Intelligence

Quayola and Akten’s Forms takes motion-capture footage of elite athletes and turns it into these dense, abstract geometries that still somehow feel like bodies moving through space. The project is explicitly framed as a “series of studies on human motion,” drawing on early motion photography by Muybridge and Marey, as well as Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase.

Instead of using a neural net to “style-transfer” an image, they use algorithmic rules to pull trajectories and forces out of video and re-inscribe them as lines, planes, and ribbons. What I got from this is a sense of “neural aesthetics” that isn’t just about training a model on a dataset, but about thinking structurally: how movement, abstraction, and reference to art history can all be encoded in a computational system.

Paglen’s From “Apple” to “Anomaly” (Pictures and Labels) made the dataset side of our lectures feel very real. The installation fills a curved gallery wall with around 30,000 printed images taken from the ImageNet training set, arranged by their category labels. Up close, you can see how messy and biased the categories are – everyday snapshots, stock photos, and deeply problematic labels all sitting together in this endless mosaic. We’d just been talking about how CNNs learn from labeled images at huge scale, and this work basically forces you to stand inside that training data. For me, it shifted “dataset bias” from an abstract problem into a visual and emotional experience: you feel how casually people’s faces and bodies have been turned into raw material for machine vision.

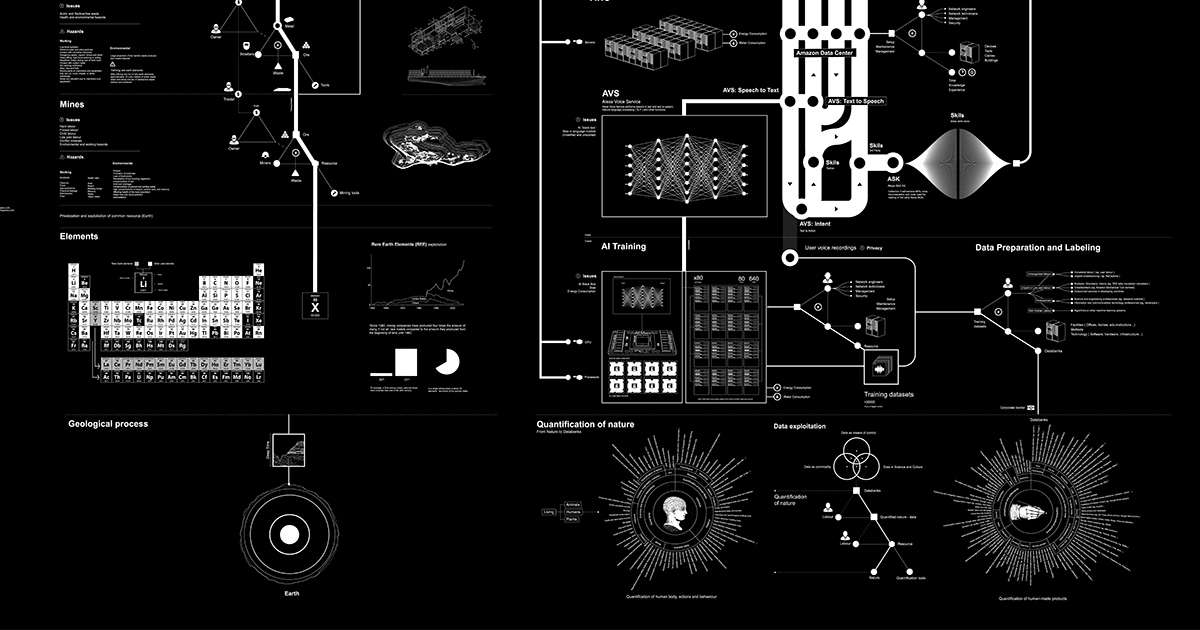

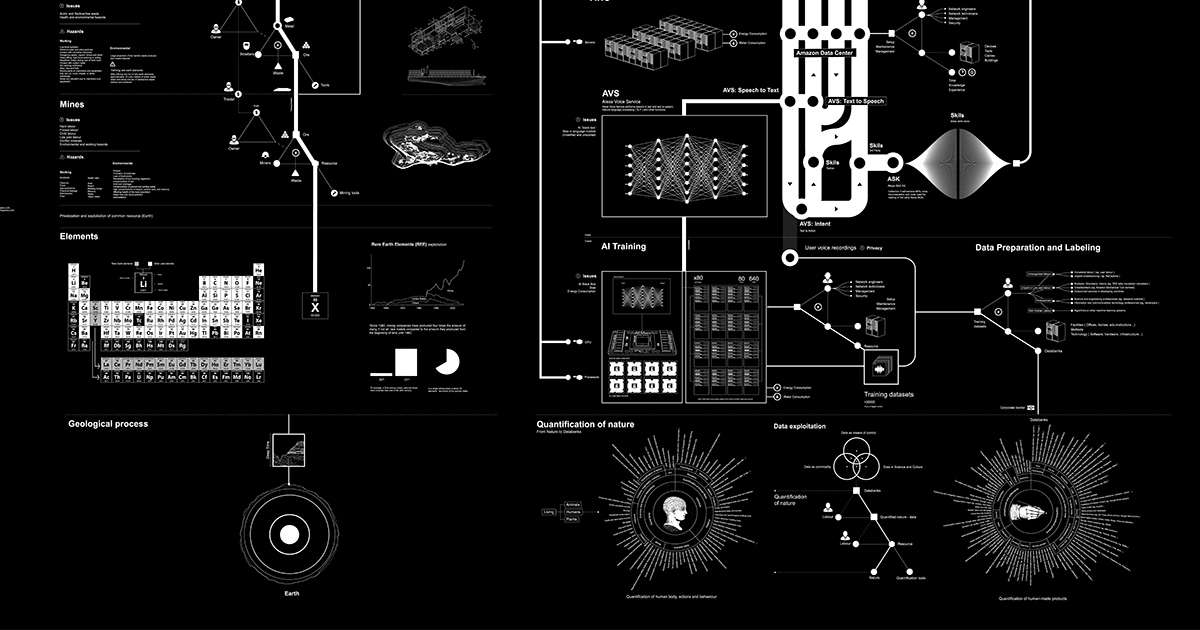

Crawford and Joler’s Anatomy of an AI System zooms out even further. It’s a giant diagram and essay that uses one Amazon Echo as a case study, mapping all the resource extraction, labor, logistics, data flows, and infrastructure that make a “smart” speaker possible.

Anatomy of an AI System. Instead of focusing on the model architecture (CNN vs. transformer, etc.), they map the planetary system around it: mines, factories, undersea cables, Mechanical Turk workers, server farms. This sits alongside Crawford’s Atlas of AI, where she argues that AI is fundamentally a technology of extraction, from minerals to low-paid data work.

Kate Crawford What I took from this is that any conversation about “intelligence” in art or AI has to keep that material and political backdrop in view; otherwise it’s too easy to treat neural networks as disembodied magic.

Instead of using a neural net to “style-transfer” an image, they use algorithmic rules to pull trajectories and forces out of video and re-inscribe them as lines, planes, and ribbons. What I got from this is a sense of “neural aesthetics” that isn’t just about training a model on a dataset, but about thinking structurally: how movement, abstraction, and reference to art history can all be encoded in a computational system.

Paglen’s From “Apple” to “Anomaly” (Pictures and Labels) made the dataset side of our lectures feel very real. The installation fills a curved gallery wall with around 30,000 printed images taken from the ImageNet training set, arranged by their category labels. Up close, you can see how messy and biased the categories are – everyday snapshots, stock photos, and deeply problematic labels all sitting together in this endless mosaic. We’d just been talking about how CNNs learn from labeled images at huge scale, and this work basically forces you to stand inside that training data. For me, it shifted “dataset bias” from an abstract problem into a visual and emotional experience: you feel how casually people’s faces and bodies have been turned into raw material for machine vision.

Crawford and Joler’s Anatomy of an AI System zooms out even further. It’s a giant diagram and essay that uses one Amazon Echo as a case study, mapping all the resource extraction, labor, logistics, data flows, and infrastructure that make a “smart” speaker possible.

Anatomy of an AI System. Instead of focusing on the model architecture (CNN vs. transformer, etc.), they map the planetary system around it: mines, factories, undersea cables, Mechanical Turk workers, server farms. This sits alongside Crawford’s Atlas of AI, where she argues that AI is fundamentally a technology of extraction, from minerals to low-paid data work.

Kate Crawford What I took from this is that any conversation about “intelligence” in art or AI has to keep that material and political backdrop in view; otherwise it’s too easy to treat neural networks as disembodied magic.

Re: wk8 11.11/11.13: Artificial Neural Networks | CNN | Style Transfer, Artificial Intelligence

Fencing Hallucination---Weihao Qiu

I’ve always been very interested in using machine learning to transform art creation. I believe this field has a lot of potential and is very promising. I previously wrote a review article on machine learning-based jazz music composition methods, titled “Analysis The Approaches and Applications for Jazz Music Composing Based on Machine Learning.” This article thoroughly analyzed the applications of various machine learning models in music composition. Through writing this paper, I realized how much potential machine learning holds in the creative arts.

Fencing Hallucination is a very interesting piece. Weihao used machine learning models, especially Pose Estimation techniques (like OpenPose), to extract the skeletal data of the audience. The AI system can capture the audience's movements in real time and generate corresponding virtual fencing poses. I think this piece really demonstrates how computer vision and neural networks can drive innovation in dynamic visual art. Weihao uses neural networks and real-time motion synthesis to transform human movement into a virtual AI fencer, responding to the audience's actions and creating a new interactive experience and an incredible artistic experience. Weihao responds to and challenges traditional photographic techniques with AI-generated imagery—the way we approach visual art in the 21st century. It even brings us to reflect on how visual art should evolve in today’s ever-developing technological landscape. Forms ----Quayola and Memo Akten (Artists)

Forms is a work that won the prestigious Golden Nica in the 2013 Prix Ars Electronica Animation category. Through its exploration of human motion, it presents the subtle relationships between the body, space, and time. The work draws inspiration from the studies of pioneers such as Eadweard Muybridge, Harold Edgerton, and Étienne-Jules Marey, while also incorporating elements from modernist cubist works, like Marcel Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase No.2. It uses cutting-edge motion tracking and simulation technologies to create dynamic sculptures that go beyond the physical limits of the body, capturing the unique qualities of movement.

What I find most fascinating about Forms is how it uses technology to combine human movement with space, revealing hidden relationships that we usually fail to notice. The piece breaks through the boundaries of traditional visual art, not merely representing motion but deeply exploring the interaction between the body and its surrounding environment. This abstract approach, using technology, delivers a powerful visual impact and has given me a new understanding of the connection between the body, technology, and art.

I’ve always been very interested in using machine learning to transform art creation. I believe this field has a lot of potential and is very promising. I previously wrote a review article on machine learning-based jazz music composition methods, titled “Analysis The Approaches and Applications for Jazz Music Composing Based on Machine Learning.” This article thoroughly analyzed the applications of various machine learning models in music composition. Through writing this paper, I realized how much potential machine learning holds in the creative arts.

Fencing Hallucination is a very interesting piece. Weihao used machine learning models, especially Pose Estimation techniques (like OpenPose), to extract the skeletal data of the audience. The AI system can capture the audience's movements in real time and generate corresponding virtual fencing poses. I think this piece really demonstrates how computer vision and neural networks can drive innovation in dynamic visual art. Weihao uses neural networks and real-time motion synthesis to transform human movement into a virtual AI fencer, responding to the audience's actions and creating a new interactive experience and an incredible artistic experience. Weihao responds to and challenges traditional photographic techniques with AI-generated imagery—the way we approach visual art in the 21st century. It even brings us to reflect on how visual art should evolve in today’s ever-developing technological landscape. Forms ----Quayola and Memo Akten (Artists)

Forms is a work that won the prestigious Golden Nica in the 2013 Prix Ars Electronica Animation category. Through its exploration of human motion, it presents the subtle relationships between the body, space, and time. The work draws inspiration from the studies of pioneers such as Eadweard Muybridge, Harold Edgerton, and Étienne-Jules Marey, while also incorporating elements from modernist cubist works, like Marcel Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase No.2. It uses cutting-edge motion tracking and simulation technologies to create dynamic sculptures that go beyond the physical limits of the body, capturing the unique qualities of movement.

What I find most fascinating about Forms is how it uses technology to combine human movement with space, revealing hidden relationships that we usually fail to notice. The piece breaks through the boundaries of traditional visual art, not merely representing motion but deeply exploring the interaction between the body and its surrounding environment. This abstract approach, using technology, delivers a powerful visual impact and has given me a new understanding of the connection between the body, technology, and art.

-

felix_yuan

- Posts: 9

- Joined: Wed Oct 01, 2025 2:40 pm

Re: wk8 11.11/11.13: Artificial Neural Networks | CNN | Style Transfer, Artificial Intelligence

My interest in AI or machine learning falls in the forms and materials that would be otherwise impossible or difficult to realize without it. Just as how at early ages of how the artists realized the aesthetic potentials behind the visualized curve lines that represents mathematical ideas or physical phenomenons, with machine learning algorithm or AI system, we can think in the same way that starts from what AI can do as a new way of computing in engineering or daily use, to what the form tool itself carries what kind of artistic potential. In this way we will go from generating images faster, easier and in a more realistic way to discover what’s special about certain technology approach itself.

Throughout the quarter we’ve seen a lot of AI related work, and the rise of how AI art becomes a hot topic, and how the topic cooled down a little. For me what’s special about AI is how it can give decision process to a not alive object, or agents, how it can make a system more real-timed and expand the possible space of the outcome in a huge extent, and the process of the neural network itself.

I would personally take Forms (2011) as a conterexample of this. Inspired by Nude Descending a Stair Case by Duchamp, this work feels less persuasive or seems unnecessary to some extent. The AI system here, even though make the system more interactive and more real-timed, does not give the work too much more content in terms of the idea of representing dynamic motion series, and looks more like a replicate or re-doing work that can also be done without AI.

Trevor Paglen’s AI dataset hypnosis is a great example of revealing the form itself. By showing the original data and how you are possibly a data point in the AI system, the view of how AI sees human world is inspiring and new.

One other fun example is the Second Me project (https://home.second.me/). Second Me is a personal AI helper that, instead of trying to learn every data from the world and keep building the model bigger and bigger and more and more general, Second Me treat the training process of AI as a long term interaction of the user. In Second Me users talk with Second Me all the time, from writing important work document to random daily notes and shopping lists, and telling the AI what are you eating today, what dream you had last night, what random thought just kicked in at what kind of moment. And day by day, as user feed the AI so many information, much more than a people can possibly tell any other person, the second me AI gradually become possibly the system, if not being called as a “person”, that knows the user the best in the world, more than anyone on earth, and possibly more than the user itself.

The interesting part in this is that by fully exposing ourselves to a machine, we get to know what ourself looks like in a machine mind, a mind that works so differently to ourself.

The idea might sound creepy at this moment given the fact that you’re giving all your data to a machine, and it could possibly pick up your phone call for you someday and make decision for your life. But it does provide an interesting view in both the relation of us and AI, and the relation of the perceived reality and the data constructed reality.

Throughout the quarter we’ve seen a lot of AI related work, and the rise of how AI art becomes a hot topic, and how the topic cooled down a little. For me what’s special about AI is how it can give decision process to a not alive object, or agents, how it can make a system more real-timed and expand the possible space of the outcome in a huge extent, and the process of the neural network itself.

I would personally take Forms (2011) as a conterexample of this. Inspired by Nude Descending a Stair Case by Duchamp, this work feels less persuasive or seems unnecessary to some extent. The AI system here, even though make the system more interactive and more real-timed, does not give the work too much more content in terms of the idea of representing dynamic motion series, and looks more like a replicate or re-doing work that can also be done without AI.

Trevor Paglen’s AI dataset hypnosis is a great example of revealing the form itself. By showing the original data and how you are possibly a data point in the AI system, the view of how AI sees human world is inspiring and new.

One other fun example is the Second Me project (https://home.second.me/). Second Me is a personal AI helper that, instead of trying to learn every data from the world and keep building the model bigger and bigger and more and more general, Second Me treat the training process of AI as a long term interaction of the user. In Second Me users talk with Second Me all the time, from writing important work document to random daily notes and shopping lists, and telling the AI what are you eating today, what dream you had last night, what random thought just kicked in at what kind of moment. And day by day, as user feed the AI so many information, much more than a people can possibly tell any other person, the second me AI gradually become possibly the system, if not being called as a “person”, that knows the user the best in the world, more than anyone on earth, and possibly more than the user itself.

The interesting part in this is that by fully exposing ourselves to a machine, we get to know what ourself looks like in a machine mind, a mind that works so differently to ourself.

The idea might sound creepy at this moment given the fact that you’re giving all your data to a machine, and it could possibly pick up your phone call for you someday and make decision for your life. But it does provide an interesting view in both the relation of us and AI, and the relation of the perceived reality and the data constructed reality.

Re: wk8 11.11/11.13: Artificial Neural Networks | CNN | Style Transfer, Artificial Intelligence

This week, what left the deepest impression on me was Fencing Hallucination by Qiu Weihao. The striking element of this piece is how it brings media art and AI together to reimagine early photographic techniques. Through encouraging AI avatars with a series of physical movements of viewers, itineraries of motion, from mechanical to computation-driven interpretation, are explored. This also adds a better understanding of what contemporary imagery would comprise, that being a pictorial expression of this indraught of motion, of human motion and machine deduction. Poetically, Weihao has brought back questions about the boundaries of time and space, in which images would “capture truth” rather than merely serve as a mere carrier of projections.

The second example, that of computer vision as evidenced by Trevor Paglen in conjunction with FIFA World Cup tracking technology, illustrates a completely different visual paradigm. In this paradigm, players are no longer considered as individuals; in this case, individuals are reduced to data points that are bounded by boxes, paths, and tags. The visual paradigm functions in such a way as to break down the world into classifiable units in a manner that seeks to optimize prediction, surveillance, and automation. This example illustrates, in a compelling fashion, how the machine gaze observes humanity and how this machine perception creates parallel realities that are beyond the realm of human observation but are progressively shaping choice, behavior, and infrastructure. There remains a fundamental visual conflict in this example in that it contends that machine vision provides a representation of reality that has computational priorities.

Finally, Hito Steyerl’s Power Plants enacts a realm of soft, near-future animation produced through neural networks. These radiant botanical entities, projected upon vertical screens, promote a different visual discourse for machine learning that derives from a sense of speculative, poetic, and even environmental knowledge, rather than purely functional ones. Steyerl brings together natural and computational worlds to interrogate how artificial intelligence thinks about life, rather than merely monitoring it. This installation urges viewers to enter a hybrid world where machine imagery has been completely incorporated into their experiential sphere.

The second example, that of computer vision as evidenced by Trevor Paglen in conjunction with FIFA World Cup tracking technology, illustrates a completely different visual paradigm. In this paradigm, players are no longer considered as individuals; in this case, individuals are reduced to data points that are bounded by boxes, paths, and tags. The visual paradigm functions in such a way as to break down the world into classifiable units in a manner that seeks to optimize prediction, surveillance, and automation. This example illustrates, in a compelling fashion, how the machine gaze observes humanity and how this machine perception creates parallel realities that are beyond the realm of human observation but are progressively shaping choice, behavior, and infrastructure. There remains a fundamental visual conflict in this example in that it contends that machine vision provides a representation of reality that has computational priorities.

Finally, Hito Steyerl’s Power Plants enacts a realm of soft, near-future animation produced through neural networks. These radiant botanical entities, projected upon vertical screens, promote a different visual discourse for machine learning that derives from a sense of speculative, poetic, and even environmental knowledge, rather than purely functional ones. Steyerl brings together natural and computational worlds to interrogate how artificial intelligence thinks about life, rather than merely monitoring it. This installation urges viewers to enter a hybrid world where machine imagery has been completely incorporated into their experiential sphere.