Human agency versus mechanical performance has long been a continuous discussion in both art and science, and it remains a source of inspiration for many media art practices. I am particularly drawn to the question of how natural life forms (patterns, unpredictability, and emotional depth) can be transformed, recreated or generated through mechanical and computational systems, and what this means for our understanding of creativity, evolution, and sentience.

In early generative art, the artist’s role was still close to that of a programmer or mathematician: the rules were written by hand, diagrams were deterministic, and the system’s autonomy was limited. Yet, even at this stage, artists were already searching for ways to let the machine become a partner in creation rather than a tool. In the 1960s, Gottfried Jäger’s concept of

Generative Photography proposed that artists could construct “aesthetic states” through mechanical and chemical processes rather than capturing reality, echoing Max Bense’s

Generative Aesthetics. Decades later, digital artists expanded this logic into algorithmic and data-driven systems that could not only execute rules but also adapt, learn, and evolve.

The notion of

evolution, once rooted in biology, now extends into computation. For machines, to evolve means to learn, to adjust internal states in response to feedback. In

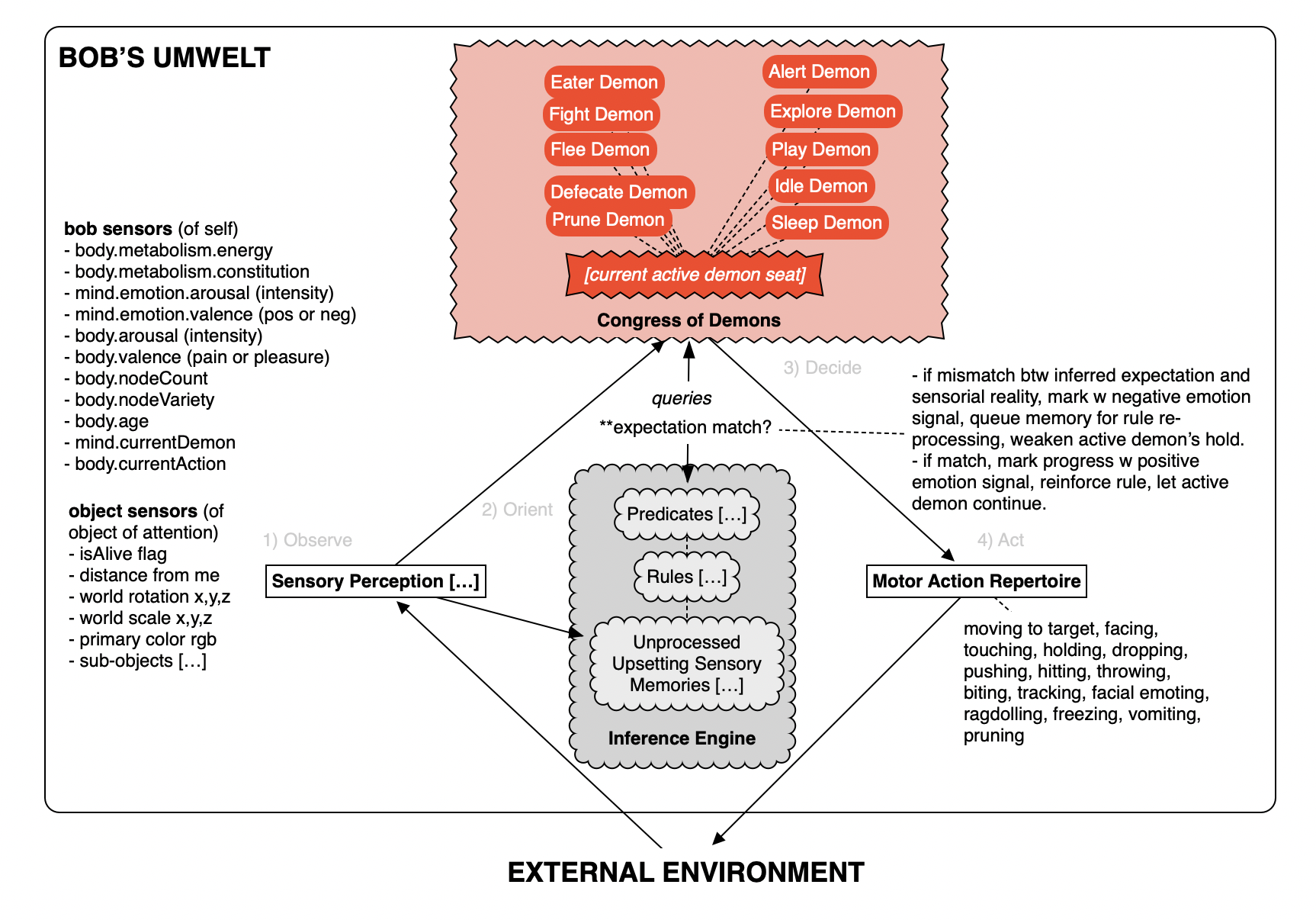

BOB (Bag of Beliefs) (2018) (Fig.1), artist Ian Cheng creates a hybrid virtual life form governed by a set of competing “demons,” each responsible for different behaviors such as feeding, exploring, fleeing, or resting. What fascinates me is that

BOB does not simply execute code; it continuously updates its beliefs through interaction with real humans. Cheng does not sculpt

BOB’s form; he sculpts the conditions for its learning. In doing so, he transforms code into ecology, suggesting that human and machine now coevolve within the same cognitive environment.

Fig.1. Ian Cheng, BOB (Bag of Beliefs) (2018)

Fig.1. Ian Cheng, BOB (Bag of Beliefs) (2018)

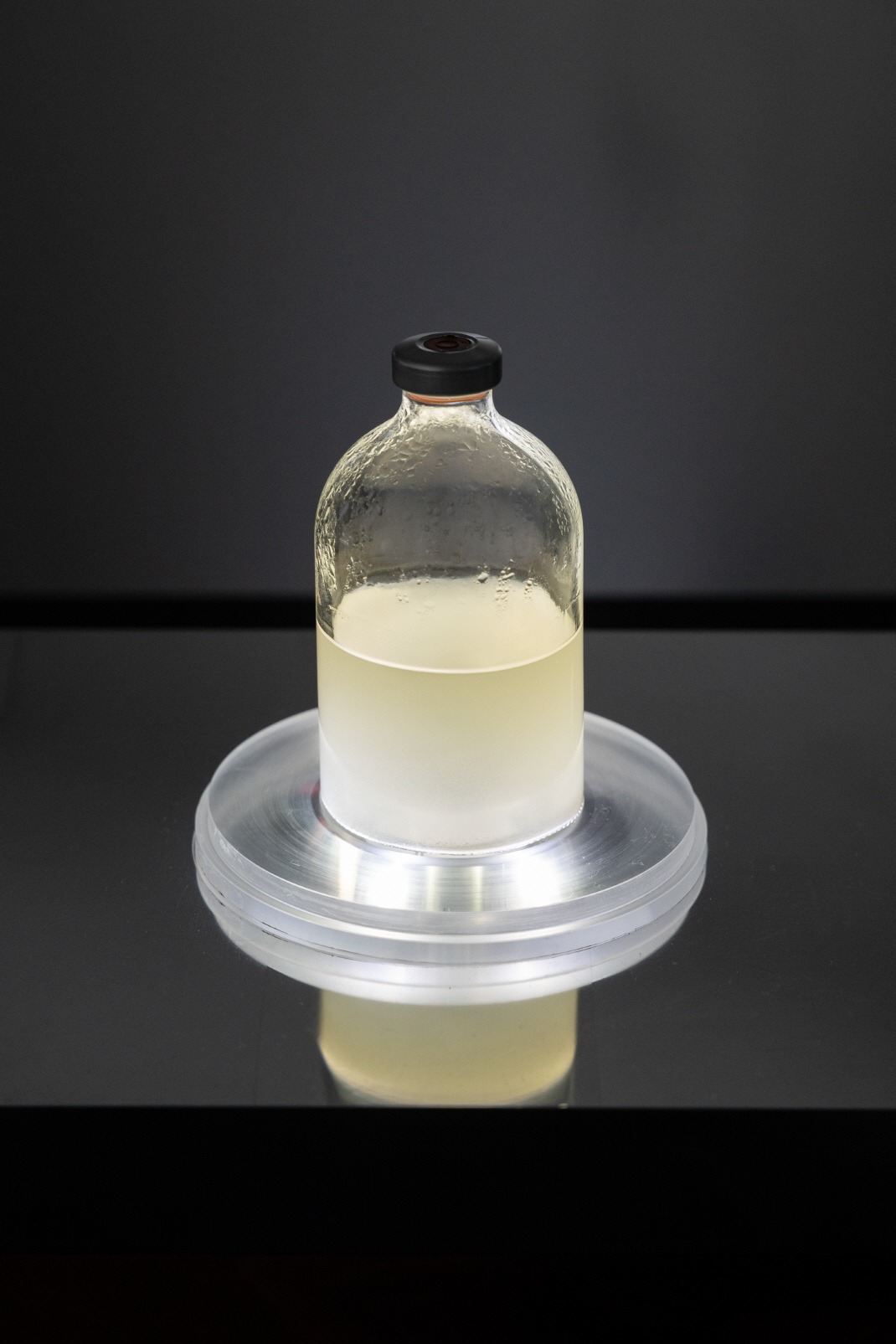

This theme of coevolution between human and nonhuman entities reappears in Eduardo Kac’s

Natural History of the Enigma (2003) (Fig.2) and Sougwen Chung’s

Realm of Silk (2023) (Fig.3). In

Edunia, Kac embedded a fragment of his own DNA into a petunia, creating a living hybrid whose red veins symbolically carry his blood. Meanwhile, in

Realm of Silk, Chung performs with four AI-powered robotic arms that move and paint alongside her on stage, enacting a choreography of shared authorship. Both artists challenge us to reconsider where “the human” ends and “the natural” begins, suggesting that identity is not fixed but constantly reassembled across biological and technological boundaries.

Fig.2. Eduardo Kac, Natural History of the Enigma (2003)

Fig.2. Eduardo Kac, Natural History of the Enigma (2003)

Fig.3. Sougwen Chung, Realm of Silk (2023)

Fig.3. Sougwen Chung, Realm of Silk (2023)

Yet as biological data becomes manipulable, questions of privacy and ethics evoke. By collecting discarded objects such as gum, hair, or cigarette butts from public spaces and extracting DNA to 3D-print faces, Heather Dewey-Hagborg’s

Stranger Visions (2013) (Fig.4) exposes how data has become the body itself. Are what we leave behind ever truly gone? What used to be invisible biological traces have become readable codes, potentially reconstructing our likeness without consent. In the age of machine learning, where every fragment of information becomes training material, we might ask what happens when our biological remains begin to “learn us” back and become deadly weapons against ourselves.

Fig.4. Heather Dewey-Hagborg, Stranger Visions (2013)

Fig.4. Heather Dewey-Hagborg, Stranger Visions (2013)

In a word, I believe that no matter how we coexist and coevolve with both nature and machines in the future, we must continue to reflect on our connections, to experiment with empathy and respect, and to seek a balance that sustains our shared well-being.