wk2 09.30/10.02: Early References

wk2 09.30/10.02: Early References

wk2 09.30/10.02: Early References

M200a course URL: https://www.mat.ucsb.edu/~g.legrady/aca ... f200a.html

Select one or more topics covered on Thursday, October 2, "The Early References".

Describe the artist, or exhibition, or publication and in a few paragraphs provide some analysis or response to the material covered. You can add additional links, or images using the Atachment function below.

M200a course URL: https://www.mat.ucsb.edu/~g.legrady/aca ... f200a.html

Select one or more topics covered on Thursday, October 2, "The Early References".

Describe the artist, or exhibition, or publication and in a few paragraphs provide some analysis or response to the material covered. You can add additional links, or images using the Atachment function below.

George Legrady

legrady@mat.ucsb.edu

legrady@mat.ucsb.edu

-

ericmrennie

- Posts: 5

- Joined: Wed Oct 01, 2025 2:33 pm

Re: wk2 09.30/10.02: Early References

Harold Cohen was a British-born artist who moved to San Diego in 1968 and later became a professor at UC San Diego. It was there that he developed his famous computer software, AARON - “a computer program designed to produce paintings and drawings autonomously, which sets it apart from previous programs” (“Harold Cohen (artist)”).

Cohen began developing AARON in the C programming language but switched to Lisp for greater flexibility. While AARON cannot learn new styles or imagery without being explicitly coded by Cohen, it can generate artworks within the parameters it has been given, developing a style of its own. In the 1970s, AARON created abstract drawings that grew in intricacy. By the 1980s, more figurative imagery, such as rocks, plants, and people appeared. In the 1990s, AARON’s figures were set within interior scenes and drawn in color. AARON returned to drawing abstract images in the 2000s - this time in color. These artworks were created by machines such as “turtle” and flatbed plotter devices (“AARON”).

I had the pleasure of visiting the Whitney Museum in New York when Cohen’s AARON exhibit was on display. There, I got to see the progression of AARON’s artworks across decades and view the software being used, connected to a pen plotter producing new works in real time. Since Cohen is credited as the first artist to use artificial intelligence in art, I found the exhibit especially poignant in today’s age of AI-generated imagery. I left the exhibit asking myself: Who is the artist? Cohen, since he programmed AARON? AARON, since it generates images within the rules it was given? Or is it a collaboration between human and machine?

These questions resonate with today’s conversations about AI art. When AI creates an image from a prompt, is the author the algorithm or the person guiding it? Is it truly “art"? Cohen posed a similar question - “If what AARON is making is not art, what is it exactly, and in what ways, other than its origin, does it differ from the ‘real thing?’” ("AARON").

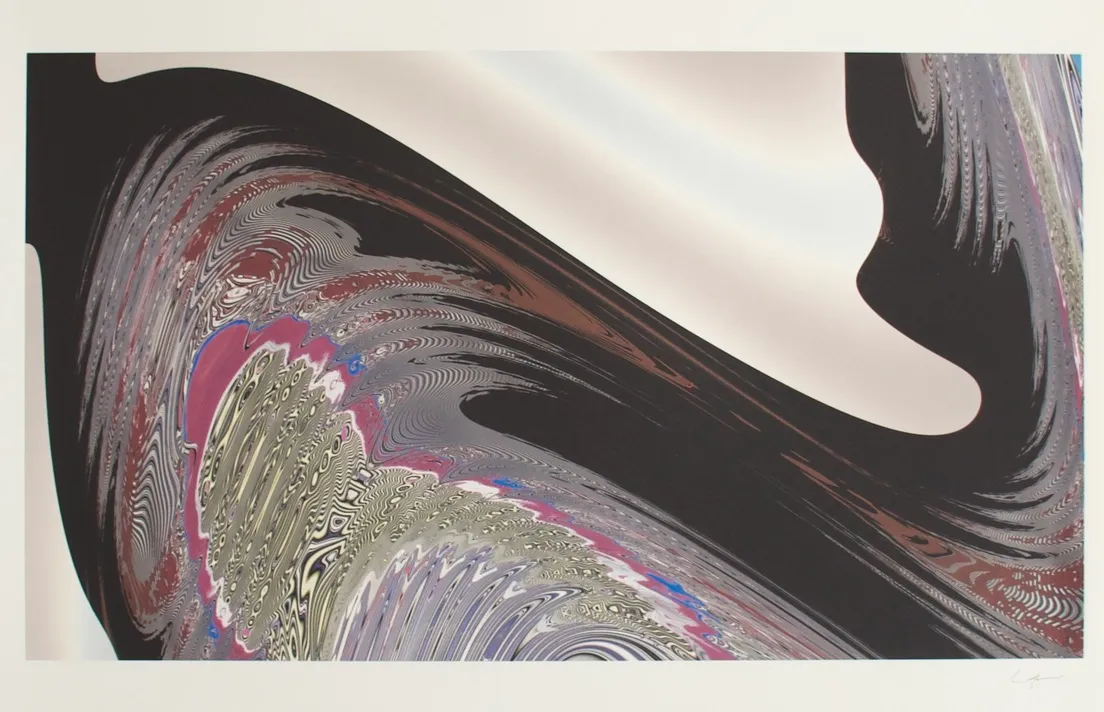

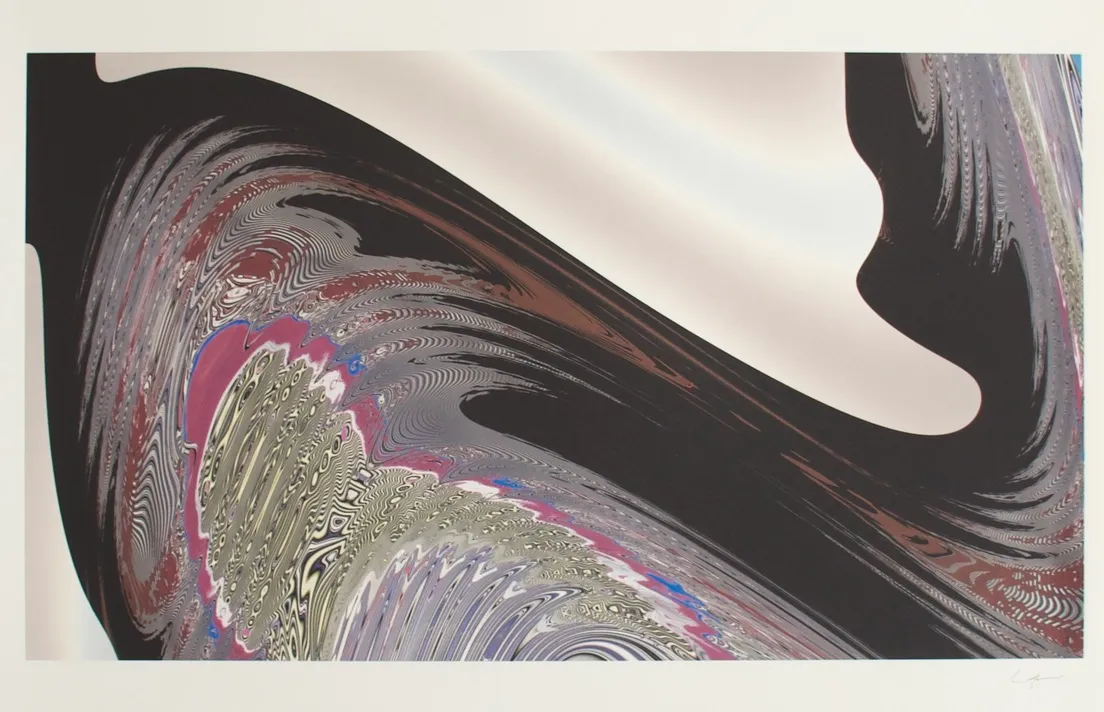

A picture I took at the Whitney Museum of Harold Cohen's "Untitled" (1986)

Works Cited

Harold Cohen (artist). Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harold_Cohen_(artist). Accessed 4 Oct. 2025.

AARON. Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/AARON. Accessed 4 Oct. 2025.

Cohen began developing AARON in the C programming language but switched to Lisp for greater flexibility. While AARON cannot learn new styles or imagery without being explicitly coded by Cohen, it can generate artworks within the parameters it has been given, developing a style of its own. In the 1970s, AARON created abstract drawings that grew in intricacy. By the 1980s, more figurative imagery, such as rocks, plants, and people appeared. In the 1990s, AARON’s figures were set within interior scenes and drawn in color. AARON returned to drawing abstract images in the 2000s - this time in color. These artworks were created by machines such as “turtle” and flatbed plotter devices (“AARON”).

I had the pleasure of visiting the Whitney Museum in New York when Cohen’s AARON exhibit was on display. There, I got to see the progression of AARON’s artworks across decades and view the software being used, connected to a pen plotter producing new works in real time. Since Cohen is credited as the first artist to use artificial intelligence in art, I found the exhibit especially poignant in today’s age of AI-generated imagery. I left the exhibit asking myself: Who is the artist? Cohen, since he programmed AARON? AARON, since it generates images within the rules it was given? Or is it a collaboration between human and machine?

These questions resonate with today’s conversations about AI art. When AI creates an image from a prompt, is the author the algorithm or the person guiding it? Is it truly “art"? Cohen posed a similar question - “If what AARON is making is not art, what is it exactly, and in what ways, other than its origin, does it differ from the ‘real thing?’” ("AARON").

A picture I took at the Whitney Museum of Harold Cohen's "Untitled" (1986)

Works Cited

Harold Cohen (artist). Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harold_Cohen_(artist). Accessed 4 Oct. 2025.

AARON. Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/AARON. Accessed 4 Oct. 2025.

Re: wk2 09.30/10.02: Early References

The article I want to discuss is 'Visual Intelligence: The First Decade of Computer Art (1965-1975)’ —Frank Dietrich

What I found so interesting about this article was its focus on the period between 1965 and 1975. It paints a vivid picture of a time when the technology was still very basic, yet you can feel the immense passion people had for trying to connect science and art. The article does a fantastic job of telling the stories from that early period and showing why it was such a foundational time.

As a student who mostly comes from a sound and music background, my knowledge of visual aesthetics has always been a bit weak. This article was a huge help in building a better foundation for me. It really helped me see the evolution of computer art. For instance, I learned that while early critics pointed out the art's "cool and mechanical look", this wasn't a failure of creativity. Instead, it was a deliberate conceptual choice by the artists, who used the computer's "nonhumanness" to break free from traditional aesthetics and cultural heritage.

The part that really stuck with me was the paradox from artist Manfred Mohr, who said his work was "formwise it is minimalist and contentwise it is maximalist”. (Fig.1) This idea was a big takeaway for me—that simple geometric shapes could hold such complex concepts. It really helped me understand what those early pioneers were trying to do.

What I found so interesting about this article was its focus on the period between 1965 and 1975. It paints a vivid picture of a time when the technology was still very basic, yet you can feel the immense passion people had for trying to connect science and art. The article does a fantastic job of telling the stories from that early period and showing why it was such a foundational time.

As a student who mostly comes from a sound and music background, my knowledge of visual aesthetics has always been a bit weak. This article was a huge help in building a better foundation for me. It really helped me see the evolution of computer art. For instance, I learned that while early critics pointed out the art's "cool and mechanical look", this wasn't a failure of creativity. Instead, it was a deliberate conceptual choice by the artists, who used the computer's "nonhumanness" to break free from traditional aesthetics and cultural heritage.

The part that really stuck with me was the paradox from artist Manfred Mohr, who said his work was "formwise it is minimalist and contentwise it is maximalist”. (Fig.1) This idea was a big takeaway for me—that simple geometric shapes could hold such complex concepts. It really helped me understand what those early pioneers were trying to do.

Last edited by ruoxi_du on Tue Oct 07, 2025 11:55 am, edited 1 time in total.

-

firving-beck

- Posts: 4

- Joined: Wed Oct 01, 2025 2:26 pm

Re: wk2 09.30/10.02: Early References

I’m interested in Deborah Hay — specifically that she takes on the role of nude model for the early computer artwork Computer Nude (Studies in Perception I), and also is a dancer/choreographer in her own right. When acting as a dancer and model, her own form becomes the subject matter, serving as a conduit for artistic ideas. Something I find really striking about conceptual/body art is the idea of the physical form being an artistic tool, versus when art is fully removed from its creator.

I chose Deborah Hay’s solo to focus on for this reason. As the choreographer, Hay dictates the movement of others. However, she is also performing as one of the dancers herself. There is something very poetic about the concept of mechanized choreography, both allowing dancers to work within specified parameters while retaining their own stylistic individuality. Is the “true” artist an autonomous agent within a system (dancer), or the author of the system (choreographer)? Both? Neither? Hay would be considered both author and agent in this case, simultaneously embodying both roles.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=J8-GAwklVFw

These questions bring to mind Sol LeWitt’s pieces, where the rules for creating an artwork are presented to gallery staff instead of the finalized piece. In this case, do the staff become artists? Are the instructions the artwork, or does the artistry truly emerge once they are carried out? This distinction becomes increasingly relevant when we consider the subject of generative/algorithmic art.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Gc-c-pYGCrw

For process based and conceptual works, the end result is often less of a priority than the endeavor of creating, itself. I could see the fleeting nature of temporal works, such as a dance performance, as being process-based to some extent, given that it is about the instantaneous movements, and there is no static endpoint. However, this is then complicated by recording technology which enables performances to be immortalized.

I chose Deborah Hay’s solo to focus on for this reason. As the choreographer, Hay dictates the movement of others. However, she is also performing as one of the dancers herself. There is something very poetic about the concept of mechanized choreography, both allowing dancers to work within specified parameters while retaining their own stylistic individuality. Is the “true” artist an autonomous agent within a system (dancer), or the author of the system (choreographer)? Both? Neither? Hay would be considered both author and agent in this case, simultaneously embodying both roles.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=J8-GAwklVFw

These questions bring to mind Sol LeWitt’s pieces, where the rules for creating an artwork are presented to gallery staff instead of the finalized piece. In this case, do the staff become artists? Are the instructions the artwork, or does the artistry truly emerge once they are carried out? This distinction becomes increasingly relevant when we consider the subject of generative/algorithmic art.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Gc-c-pYGCrw

For process based and conceptual works, the end result is often less of a priority than the endeavor of creating, itself. I could see the fleeting nature of temporal works, such as a dance performance, as being process-based to some extent, given that it is about the instantaneous movements, and there is no static endpoint. However, this is then complicated by recording technology which enables performances to be immortalized.

Last edited by firving-beck on Thu Oct 09, 2025 12:01 pm, edited 2 times in total.

Re: wk2 09.30/10.02: Early References

https://unframed.lacma.org/2025/10/01/e ... ydrophobia

Thoughts on Art and Technology, Jane Livingston — Maurice Tuchman. A Report on the Art and Technology Program of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art

The text discusses the Art and Technology (A&T) program at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) in the late 1960s, led by curator Maurice Tuchman. The project aimed to connect artists with industrial corporations to explore new creative possibilities. It explains how the idea evolved, how companies were persuaded to participate, and how artists learned to balance creative freedom with industrial collaboration—marking one of the first major efforts to merge art and innovation.

Two main artistic approaches emerged: some artists focused on industrial fabrication, while others experimented with new technological and informational media that went beyond traditional art-making. Working with industry presented challenges, as artists had to give up some control over the production process and adapt to corporate systems.

Unlike the “tech art” of the time that often relied on light or sound, the works created through the A&T program were remarkably diverse and unpredictable, reflecting each artist’s unique use of corporate tools and materials. The process was experimental and open-ended, with no single artistic or corporate agenda. This freedom allowed artists to maintain their individuality while exploring new aesthetic directions, proving that art and technology could coexist without limiting creativity.

What inspires me most about this story is Maurice Tuchman’s vision and determination to unite two very different worlds. He admitted that at first, he had no idea how to convince corporations to welcome artists into their facilities—the real question was why they should want to. Yet, in the end, he succeeded, creating a space where creativity and technological innovation could truly meet.

Explore Ecology and Extraction at a Performance and Screening of “S̶t̶r̶a̶y̶ D̶o̶g̶ Hydrophobia”

The article talks about Stray Dog Hydrophobia, a project by artists Patty Chang and David Kelley, supported by LACMA’s Art + Technology Lab. Their work blends film, live music, and performance to explore the hidden world of deep-sea mining and how it connects to centuries of colonialism, slavery, and environmental exploitation.

The artists were inspired by the International Seabed Authority (ISA) in Jamaica, which is currently deciding whether to allow deep-sea mining. They draw a direct line between today’s extractive industries and the older systems of power that shaped colonial history.

To bring these invisible stories to life, Chang and Kelley filmed in Jamaica, the UK, and Los Angeles, using both documentary and experimental tools like animation, 3D scanning, and photogrammetry. They even collaborated with scientists and students to transform deep-sea specimens into artworks, asking viewers to see the ocean not as a resource to exploit, but as a living network that connects us all.

The title, Stray Dog Hydrophobia, captures themes of freedom, fear, and ecological disruption—reflecting how human and non-human lives are deeply intertwined. Through this project, the artists invite us to rethink how progress and technology often come at the cost of the planet, and to imagine more caring, sustainable ways of being connected to the ocean and to each other.

Final thoughts

As a final reflection, I see a clear contrast between this text and the previous one. While Maurice Tuchman’s Art and Technology program viewed industry as a source of inspiration and collaboration for creating new forms of art, Patty Chang and David Kelley’s Stray Dog Hydrophobia turns that same relationship into a critique—revealing how industrial and technological power can harm cultures and the environment. Their work transforms the impact of deep-sea mining into a poetic reflection on colonialism and ecological exploitation.

After working in the industry for five years, I have collaborated closely with designers and engineers in leading roles. Now, through this master’s program and my own independent projects, I am beginning to explore the intersection of art and technology from a more critical and creative perspective. Both historical and contemporary examples show the complexity and beauty of the encounter between artists and industry. This interaction is often chaotic, shaped by contrasting values, priorities, and cultures—but from that friction, innovation and new hybrid forms of expression emerge.

I chose Stray Dog Hydrophobia by Patty Chang and David Kelley because it highlights another dimension of this relationship: the tension between corporate systems that exploit natural resources and the artists who use those same realities to expose, question, and reimagine them.

In conclusion, I see the intersection between art and industry as a space of constant tension but also immense potential. It allows artists to channel imagination and critical insight through the tools and networks of technology, creating works that are both socially engaged and technically informed.

Thoughts on Art and Technology, Jane Livingston — Maurice Tuchman. A Report on the Art and Technology Program of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art

The text discusses the Art and Technology (A&T) program at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) in the late 1960s, led by curator Maurice Tuchman. The project aimed to connect artists with industrial corporations to explore new creative possibilities. It explains how the idea evolved, how companies were persuaded to participate, and how artists learned to balance creative freedom with industrial collaboration—marking one of the first major efforts to merge art and innovation.

Two main artistic approaches emerged: some artists focused on industrial fabrication, while others experimented with new technological and informational media that went beyond traditional art-making. Working with industry presented challenges, as artists had to give up some control over the production process and adapt to corporate systems.

Unlike the “tech art” of the time that often relied on light or sound, the works created through the A&T program were remarkably diverse and unpredictable, reflecting each artist’s unique use of corporate tools and materials. The process was experimental and open-ended, with no single artistic or corporate agenda. This freedom allowed artists to maintain their individuality while exploring new aesthetic directions, proving that art and technology could coexist without limiting creativity.

What inspires me most about this story is Maurice Tuchman’s vision and determination to unite two very different worlds. He admitted that at first, he had no idea how to convince corporations to welcome artists into their facilities—the real question was why they should want to. Yet, in the end, he succeeded, creating a space where creativity and technological innovation could truly meet.

Explore Ecology and Extraction at a Performance and Screening of “S̶t̶r̶a̶y̶ D̶o̶g̶ Hydrophobia”

The article talks about Stray Dog Hydrophobia, a project by artists Patty Chang and David Kelley, supported by LACMA’s Art + Technology Lab. Their work blends film, live music, and performance to explore the hidden world of deep-sea mining and how it connects to centuries of colonialism, slavery, and environmental exploitation.

The artists were inspired by the International Seabed Authority (ISA) in Jamaica, which is currently deciding whether to allow deep-sea mining. They draw a direct line between today’s extractive industries and the older systems of power that shaped colonial history.

To bring these invisible stories to life, Chang and Kelley filmed in Jamaica, the UK, and Los Angeles, using both documentary and experimental tools like animation, 3D scanning, and photogrammetry. They even collaborated with scientists and students to transform deep-sea specimens into artworks, asking viewers to see the ocean not as a resource to exploit, but as a living network that connects us all.

The title, Stray Dog Hydrophobia, captures themes of freedom, fear, and ecological disruption—reflecting how human and non-human lives are deeply intertwined. Through this project, the artists invite us to rethink how progress and technology often come at the cost of the planet, and to imagine more caring, sustainable ways of being connected to the ocean and to each other.

Final thoughts

As a final reflection, I see a clear contrast between this text and the previous one. While Maurice Tuchman’s Art and Technology program viewed industry as a source of inspiration and collaboration for creating new forms of art, Patty Chang and David Kelley’s Stray Dog Hydrophobia turns that same relationship into a critique—revealing how industrial and technological power can harm cultures and the environment. Their work transforms the impact of deep-sea mining into a poetic reflection on colonialism and ecological exploitation.

After working in the industry for five years, I have collaborated closely with designers and engineers in leading roles. Now, through this master’s program and my own independent projects, I am beginning to explore the intersection of art and technology from a more critical and creative perspective. Both historical and contemporary examples show the complexity and beauty of the encounter between artists and industry. This interaction is often chaotic, shaped by contrasting values, priorities, and cultures—but from that friction, innovation and new hybrid forms of expression emerge.

I chose Stray Dog Hydrophobia by Patty Chang and David Kelley because it highlights another dimension of this relationship: the tension between corporate systems that exploit natural resources and the artists who use those same realities to expose, question, and reimagine them.

In conclusion, I see the intersection between art and industry as a space of constant tension but also immense potential. It allows artists to channel imagination and critical insight through the tools and networks of technology, creating works that are both socially engaged and technically informed.

Last edited by italo on Mon Oct 13, 2025 8:47 pm, edited 1 time in total.

-

jcrescenzo

- Posts: 4

- Joined: Wed Oct 01, 2025 2:17 pm

Re: wk2 09.30/10.02: Early References

Seek by the Architecture Machine group, housed gerbils surrounded by metal blocks. The gerbils move the blocks and a robotic arm reacts and stacked the blocks in a grid-like fashion. In theory, the gerbils design and the robot Seek helps tidy up. The robot is trying to anticipate (predict) the next intention and assist, not unlike how we imagine this relationship between AI (machine prediction) and human activity.

In the Jetsons, the future is full of helpful machines.

https://www.adweek.com/commerce/roomba- ... e-jetsons/

There is also the reverse relationship, the “less sunnier side.” Instead of the machine serving their gerbils’ preferences, we could imagine a relationship where the gerbils are constantly working against the machine.

Ted Nelson, pioneer of hypertext, and fellow attendee at the Jewish Museum Exhibit, wrote “I remember watching one gerbil who stood motionless on his little kangaroo matchstick legs, watching the Great Grappler rearranging his world.”

Maybe the gerbils don’t want their environment, their home arranged in a grid fashion. Maybe the gerbils are frustrated with the machine, afraid of it, but they simply have to live with it.

The Architecture Machine group is out of MIT University, the same place they developed numerical control, the auto control of machine tools.

Technology historian, David Noble explains how the adoption of"numerical control" https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Computer_ ... al_control was not more efficient than analog control systems in his book Forces of Production. The shift from analog to numerical control manufacturing was protested by workers at the time, but compelled by corporations and the US military. The analogies to “AI” technology and the situation today is illuminating.

https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/mon ... avid-noble

When we think of “AI” technologies, the machine does not do anything out of spite but is imposed on us. This was certainly not the intention of the group, but it is prescient today.

In the Jetsons, the future is full of helpful machines.

https://www.adweek.com/commerce/roomba- ... e-jetsons/

There is also the reverse relationship, the “less sunnier side.” Instead of the machine serving their gerbils’ preferences, we could imagine a relationship where the gerbils are constantly working against the machine.

Ted Nelson, pioneer of hypertext, and fellow attendee at the Jewish Museum Exhibit, wrote “I remember watching one gerbil who stood motionless on his little kangaroo matchstick legs, watching the Great Grappler rearranging his world.”

Maybe the gerbils don’t want their environment, their home arranged in a grid fashion. Maybe the gerbils are frustrated with the machine, afraid of it, but they simply have to live with it.

The Architecture Machine group is out of MIT University, the same place they developed numerical control, the auto control of machine tools.

Technology historian, David Noble explains how the adoption of"numerical control" https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Computer_ ... al_control was not more efficient than analog control systems in his book Forces of Production. The shift from analog to numerical control manufacturing was protested by workers at the time, but compelled by corporations and the US military. The analogies to “AI” technology and the situation today is illuminating.

https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/mon ... avid-noble

When we think of “AI” technologies, the machine does not do anything out of spite but is imposed on us. This was certainly not the intention of the group, but it is prescient today.

-

lucianparisi

- Posts: 4

- Joined: Thu Sep 26, 2024 2:16 pm

Re: wk2 09.30/10.02: Early References

“Japanese Computer Art and the Reality of Collecting It” exposes an entire art scene scarcely discussed today. While this was technologically and artistically influential, few of the works have been preserved. Those that have are not readily available to the public eye. According to the author, this is due to many of the early Japanese innovators being engineers , not artists. This is most prevalent in the CTG (Computer Technique Group), which contained only 1 artist. This is in direct contrast with counterpart computer art movements in Germany and other parts of Europe. This engineer vs artist culture, along with gender stigma, is cited as a potential reason for a lack of institutional adoption.

The key exception in this scene was Yoshiyuki Abe. He was steadfast in holding onto his work and not allowing it to disappear into convoluted institutions. This proves cultural valuable due to the nature of his work. Early Western computer art was rigid and unnatural. In contrast, Abe’s work was fluid and biological. Not only was Abe manufacturing his own hardware and writing his software, but he was integrating Japanese aesthetic design principles into his work. This combination feels particularly relevant to MAT students, and to my own work - I am partial toward a fluid, organic aesthetic with my visual pieces.

While Abe’s work was acclaimed in Japan, it was not a part of the cannon Cybernetic Serendipity show. Thus, it never made its way to the public eye in the West.

The key exception in this scene was Yoshiyuki Abe. He was steadfast in holding onto his work and not allowing it to disappear into convoluted institutions. This proves cultural valuable due to the nature of his work. Early Western computer art was rigid and unnatural. In contrast, Abe’s work was fluid and biological. Not only was Abe manufacturing his own hardware and writing his software, but he was integrating Japanese aesthetic design principles into his work. This combination feels particularly relevant to MAT students, and to my own work - I am partial toward a fluid, organic aesthetic with my visual pieces.

While Abe’s work was acclaimed in Japan, it was not a part of the cannon Cybernetic Serendipity show. Thus, it never made its way to the public eye in the West.

-

shashank86

- Posts: 4

- Joined: Wed Oct 01, 2025 2:36 pm

Re: wk2 09.30/10.02: Early References - resubmitted

Both CTG and Manfred Mohr connected with me a lot.

CTG (Computer Technique Group) demonstrates how late-1960s Japanese computer art used code to transform cultural images in public-facing formats such as posters, films, and plotter drawings. Works like Running Cola is Africa! show metamorphosis as both technique and metaphor, translating a moving body into a commodity into geopolitics through a single program. - https://zkm.de/en/artwork/running-cola-is-africa

I like how CTG included more evidence-based working elements as part of the art and less emphasis on pure expression. I could see them visualizing that something is working and kept expanding the technology's capabilities. From writing the code to the impressions were always collective since a group of artists and engineers formed CTG, but the same can be observed about the Japanese cultural perspective, which perfectly balanced the native and modern style. Culturally, I felt they still had a collective mentality to do things together in domains like contemporary arts (arts unlike cinema, which requires many people), similar to their industrial and technological revolution approach!

Golan Levin’s article - Interpolation in Computer Art, references Running Cola is Africa! as a precursor to exploring in-between states in computational art-artists traverse latent spaces, morphing between image states - https://medium.com/%40golanlevin/interp ... 052d997fdf

Manfred Mohr takes the opposite route by limiting the vocabulary to lines of a cube, then expanding infinitely through computation. Watching Cubic Limit (1973–74), you see how minimal elements generate maximal states—rotations, edge subsets, projections until the system feels musical. Mohr’s later surveys highlight how algorithmic constraints can sustain an entire career, moving from 3D cubes to high-dimensional hypercubes without abandoning clarity. Manfred Mohr's felt remains timeless because of the color ratio and geometric balance, and just enough motion. Whether the artist knew what exactly he was trying to do, even though it was the early times of computer graphics.

()

Still, both artists shaped a new tool's features and capabilities and defined new constraints to make things aesthetic, which I feel is one of the three best things a creator can do. CTG’s semantic metamorphoses and Mohr’s structural permutations answer the Harold Cohen/AARON question “who is the artist?” - by reframing authorship as systems design. Like Deborah Hay choreographing and dancing, these works propose an artist who both writes the rules and inhabits them. That’s why the 1960s “cool and mechanical” look (Dietrich) reads now as a value choice: art that reveals how images, rules, and cultures transform—sometimes with a plotter’s line, sometimes with a cube’s edge.

CTG (Computer Technique Group) demonstrates how late-1960s Japanese computer art used code to transform cultural images in public-facing formats such as posters, films, and plotter drawings. Works like Running Cola is Africa! show metamorphosis as both technique and metaphor, translating a moving body into a commodity into geopolitics through a single program. - https://zkm.de/en/artwork/running-cola-is-africa

I like how CTG included more evidence-based working elements as part of the art and less emphasis on pure expression. I could see them visualizing that something is working and kept expanding the technology's capabilities. From writing the code to the impressions were always collective since a group of artists and engineers formed CTG, but the same can be observed about the Japanese cultural perspective, which perfectly balanced the native and modern style. Culturally, I felt they still had a collective mentality to do things together in domains like contemporary arts (arts unlike cinema, which requires many people), similar to their industrial and technological revolution approach!

Golan Levin’s article - Interpolation in Computer Art, references Running Cola is Africa! as a precursor to exploring in-between states in computational art-artists traverse latent spaces, morphing between image states - https://medium.com/%40golanlevin/interp ... 052d997fdf

Manfred Mohr takes the opposite route by limiting the vocabulary to lines of a cube, then expanding infinitely through computation. Watching Cubic Limit (1973–74), you see how minimal elements generate maximal states—rotations, edge subsets, projections until the system feels musical. Mohr’s later surveys highlight how algorithmic constraints can sustain an entire career, moving from 3D cubes to high-dimensional hypercubes without abandoning clarity. Manfred Mohr's felt remains timeless because of the color ratio and geometric balance, and just enough motion. Whether the artist knew what exactly he was trying to do, even though it was the early times of computer graphics.

()

Still, both artists shaped a new tool's features and capabilities and defined new constraints to make things aesthetic, which I feel is one of the three best things a creator can do. CTG’s semantic metamorphoses and Mohr’s structural permutations answer the Harold Cohen/AARON question “who is the artist?” - by reframing authorship as systems design. Like Deborah Hay choreographing and dancing, these works propose an artist who both writes the rules and inhabits them. That’s why the 1960s “cool and mechanical” look (Dietrich) reads now as a value choice: art that reveals how images, rules, and cultures transform—sometimes with a plotter’s line, sometimes with a cube’s edge.

Last edited by shashank86 on Sat Oct 11, 2025 10:05 am, edited 3 times in total.

Re: wk2 09.30/10.02: Early References

The article I’m interested in is “Computer Art System: ART-3,” developed by Mutsuko and Takeaki Sasaki. I chose it because it reminds me of AutoCAD hatches and computational drawings that I draw every day without thinking about how they actually work.

ART-3 explores how algorithms can assist in creating artworks that retain the quality of hand-drawn figures. The system relies on a lattice: users draw images as input, and each lattice point is treated as a vector. Based on the input, the system deconstructs the figure into four types—lines, opaque contours, holes, and transparent contours. These data are entered on punched cards as sequences of vectors. From there, ART-3 performs transformations such as stretching, rotation, and scaling. The figures are embedded into a digital canvas with parameters controlling their position, size, and texture. The system can also apply different texture modes and produce color outputs using a plotter.

I find this system meaningful because it demonstrates an early attempt to interpret human sketches through computational rules. Growing up reading manga, I notice a similar quality between ART-3’s outputs and the expressive textures in manga sketches(usually a combination of hand sketches and texture mesh). Even though the results come from algorithmic repetition, they preserve a sense of human touch and rhythm.

ART-3 explores how algorithms can assist in creating artworks that retain the quality of hand-drawn figures. The system relies on a lattice: users draw images as input, and each lattice point is treated as a vector. Based on the input, the system deconstructs the figure into four types—lines, opaque contours, holes, and transparent contours. These data are entered on punched cards as sequences of vectors. From there, ART-3 performs transformations such as stretching, rotation, and scaling. The figures are embedded into a digital canvas with parameters controlling their position, size, and texture. The system can also apply different texture modes and produce color outputs using a plotter.

I find this system meaningful because it demonstrates an early attempt to interpret human sketches through computational rules. Growing up reading manga, I notice a similar quality between ART-3’s outputs and the expressive textures in manga sketches(usually a combination of hand sketches and texture mesh). Even though the results come from algorithmic repetition, they preserve a sense of human touch and rhythm.

Last edited by xuegao on Thu Oct 09, 2025 10:23 am, edited 2 times in total.

Re: wk2 09.30/10.02: Early References

https://www.getty.edu/news/experiments- ... -pst-art/

Experiments in Art and Technology (E.A.T.)

Collaboration has long been an established and common practice in media art. Media art emerges from an interdisciplinary fusion of art and technology, yet it is nearly impossible for one individual to master every specialized field involved. For this reason, collaboration between artists and engineers becomes an indispensable component of the creative process.

The Getty PST ART exhibition Sensing the Future explores how postwar artists and engineers sought to imagine and invent the future together.

A representative example presented in the exhibition is 9 Evenings: Theatre & Engineering, held in New York in the fall of 1966.

This large-scale collaborative project brought together ten artists and thirty engineers, including musicians, dancers, visual artists, and theater producers, who experimented with integrating what were then unprecedented technologies—such as real-time sound modulation, biofeedback, and video projection—into live performance

(Getty Newsroom, “Experiments in Art and Technology (E.A.T.),” 2024).

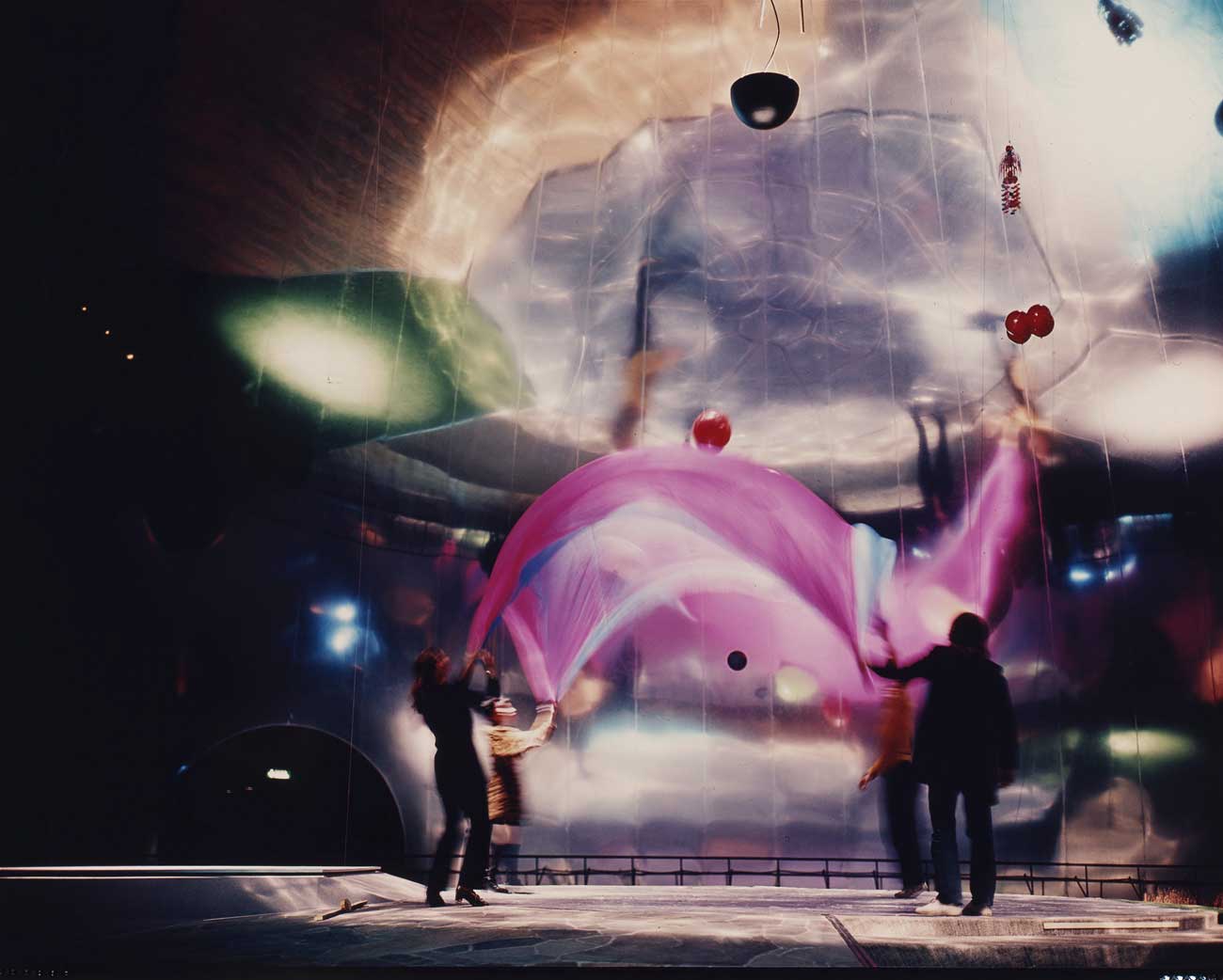

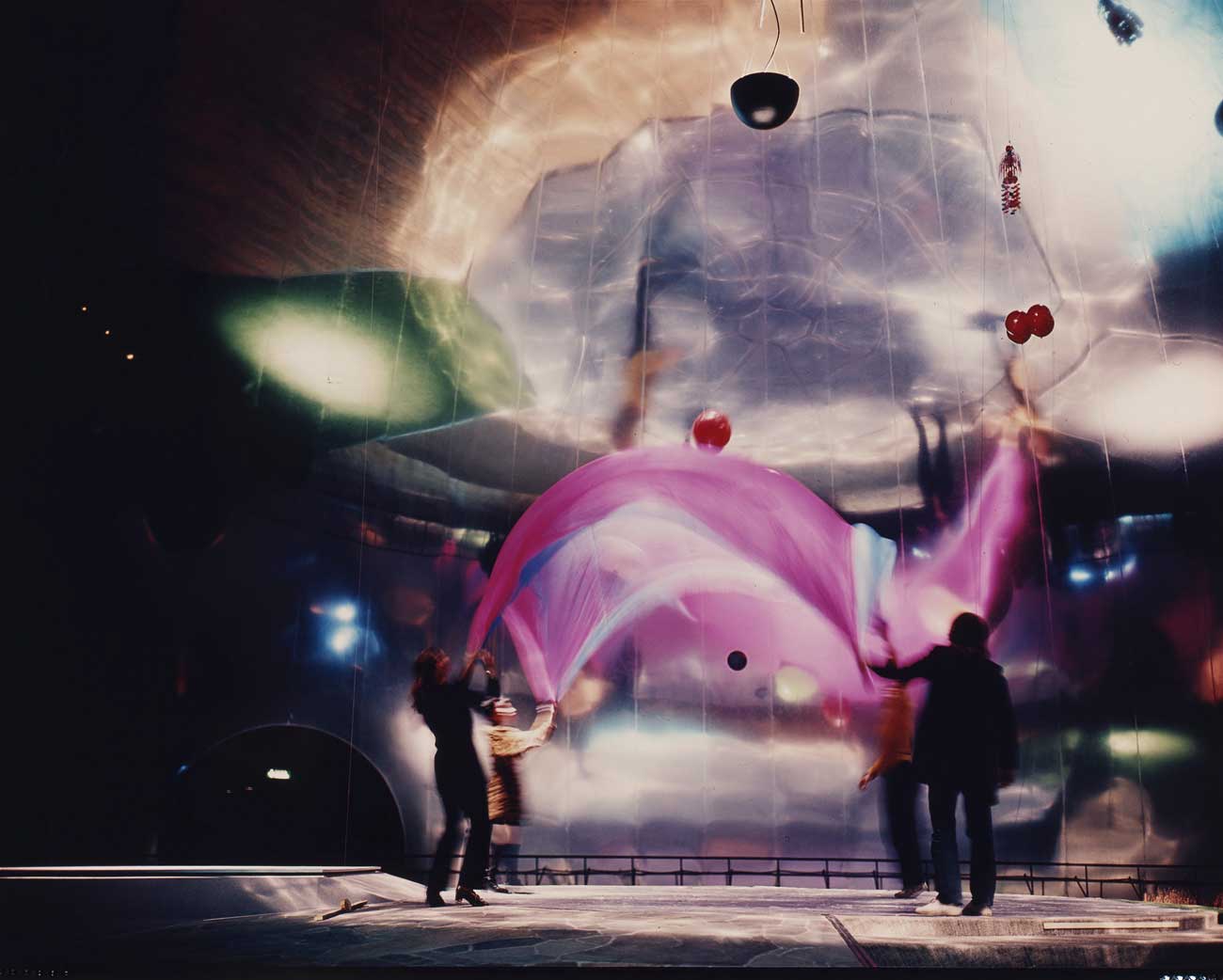

Performance inside the Pepsi-Cola Pavilion, 1970. Photograph: Shunk-Kender © J. Paul Getty Trust. Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles (2014.R.20). Gift of the Roy Lichtenstein Foundation in memory of Harry Shunk and Janos Kende

The event led to the founding of E.A.T. (Experiments in Art and Technology) by engineers Billy Klüver and Fred Waldhauer, and artists Robert Rauschenberg and Robert Whitman. Klüver, a physicist at Bell Laboratories, acted as a mediator between New York’s avant-garde artists and pioneers of technologies such as lasers, computers, and electronic sound. He and Rauschenberg wrote that “E.A.T. is founded on the strong belief that an industrially sponsored, effective working relationship between artists and engineers will lead to new possibilities which will benefit society as a whole". (Klüver & Rauschenberg, quoted in Getty, 2024).

The emergence of E.A.T. was not limited to a single performance or exhibition. Whether or not media art has truly opened new possibilities for the betterment of society remains an open question, but their collaboration demonstrated the potential for future generations of artists to incorporate technology and science into the realm of artistic practice.As a visual artist, I have also collaborated with engineers in my own projects, and I have often wondered how both sides might transcend the perception of the other as merely functional—engineers as “technical executors” and artists as “aesthetic decorators.”

In this regard, the example of E.A.T. offers profound insight. It reveals how genuine collaboration requires mutual respect and shared curiosity, rather than a division of roles based solely on technical or artistic authority. Today’s media artists and engineers can still learn from this model, recognizing that successful collaboration depends not only on technical integration but also on cultivating empathy, communication, and a shared sense of creative purpose.

Collaboration has long been an established and common practice in media art. Media art emerges from an interdisciplinary fusion of art and technology, yet it is nearly impossible for one individual to master every specialized field involved. For this reason, collaboration between artists and engineers becomes an indispensable component of the creative process.

The Getty PST ART exhibition Sensing the Future explores how postwar artists and engineers sought to imagine and invent the future together.

A representative example presented in the exhibition is 9 Evenings: Theatre & Engineering, held in New York in the fall of 1966.

This large-scale collaborative project brought together ten artists and thirty engineers, including musicians, dancers, visual artists, and theater producers, who experimented with integrating what were then unprecedented technologies—such as real-time sound modulation, biofeedback, and video projection—into live performance

(Getty Newsroom, “Experiments in Art and Technology (E.A.T.),” 2024).

Performance inside the Pepsi-Cola Pavilion, 1970. Photograph: Shunk-Kender © J. Paul Getty Trust. Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles (2014.R.20). Gift of the Roy Lichtenstein Foundation in memory of Harry Shunk and Janos Kende

The event led to the founding of E.A.T. (Experiments in Art and Technology) by engineers Billy Klüver and Fred Waldhauer, and artists Robert Rauschenberg and Robert Whitman. Klüver, a physicist at Bell Laboratories, acted as a mediator between New York’s avant-garde artists and pioneers of technologies such as lasers, computers, and electronic sound. He and Rauschenberg wrote that “E.A.T. is founded on the strong belief that an industrially sponsored, effective working relationship between artists and engineers will lead to new possibilities which will benefit society as a whole". (Klüver & Rauschenberg, quoted in Getty, 2024).

The emergence of E.A.T. was not limited to a single performance or exhibition. Whether or not media art has truly opened new possibilities for the betterment of society remains an open question, but their collaboration demonstrated the potential for future generations of artists to incorporate technology and science into the realm of artistic practice.As a visual artist, I have also collaborated with engineers in my own projects, and I have often wondered how both sides might transcend the perception of the other as merely functional—engineers as “technical executors” and artists as “aesthetic decorators.”

In this regard, the example of E.A.T. offers profound insight. It reveals how genuine collaboration requires mutual respect and shared curiosity, rather than a division of roles based solely on technical or artistic authority. Today’s media artists and engineers can still learn from this model, recognizing that successful collaboration depends not only on technical integration but also on cultivating empathy, communication, and a shared sense of creative purpose.